The Pulitzer Prize for Fiction is one of the most highly sought literary awards in the United States. Since its inception in 1917, 86 writers have won the prize—among them, some of the nation’s greatest talents. Yet not all has gone smoothly. Here are five instances where the awarding (or withholding) of the Pulitzer has erupted in controversy.

1. Sinclair Lewis

In 1921, Sinclair Lewis lost the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction despite having won the jurors’ vote. He was nominated for his novel Main Street, which was controversial for its satirical portrayal of small town America. The highly conservative Pulitzer Prize board overturned the jurors’ vote, awarding the prize instead to Edith Wharton for her novel The Age of Innocence. In order to justify their decision, the board changed the award criteria from “best presenting the whole atmosphere of American life” to “best presenting the wholesome atmosphere of American life.”

Wharton publicly criticized the Pulitzer committee when she learned of their actions and Lewis dedicated his next novel to her. In 1926, Lewis won the Pulitzer for his book Arrowsmith. He refused it, however, stating, “All prizes, like all titles, are dangerous… the Pulitzer Prize for Novels is peculiarly objectionable because the terms of it have been constantly and grievously misrepresented.”

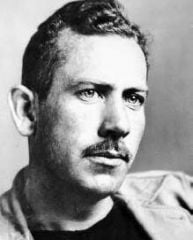

2. John Steinbeck

John Steinbeck won the Pulitzer in 1940 for his novel The Grapes of Wrath. While hailed today as one of the great American novels, at the time it was criticized and widely banned. The press and many politicians accused Steinbeck of being a socialist or communist and in some cases the book was even burned. Both popular and critical opinion was split about the novel. Many considered it brilliant, while others disparaged it. The reviewer from Newsweek called it a “mess of silly propaganda, superficial observation, careless infidelity to the proper use of idiom, tasteless pornographical and scatagorical talk.”

Steinbeck commented on the controversy saying, “The vilification of me out here from the large landowners and bankers is pretty bad. The latest is a rumor started by them that the Okies hate me and have threatened to kill me for lying about them. I'm frightened at the rolling might of this damned thing. It is completely out of hand; I mean a kind of hysteria about the book is growing that is not healthy." Although opponents to the book were incensed that it won the Pulitzer Prize, history has proven the Pulitzer committee right as The Grapes of Wrath remains one of the most important American novels today.

3. Ernest Hemingway

In 1941, the Pulitzer Prize jurors voted unanimously for Ernest Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls. Everyone was in favor of the book except for Nicholas Murray Butler, president of Columbia University and ex-officio chairman of the board. Butler vetoed the jurors’ choice, deeming the book offensive and profane. He said, “I hope that you will reconsider before you ask the University to be associated with an award for a work of this nature.” There was no fiction winner that year.

However, Hemingway did go on to win the Pulitzer in 1953 for his novel, The Old Man and the Sea. Some have interpreted Hemingway’s eventual Pulitzer more as a nod to his overall career than as an award for The Old Man and the Sea—generally considered a lesser work to For Whom the Bell Tolls.

4. William Faulkner

In 1930, the Pulitzer committee awarded the fiction prize to Oliver La Farge for his novel Laughing Boy—overlooking The Sound and the Fury by William Faulkner and A Farewell to Arms by Ernest Hemingway. Six years later, Faulkner was passed over for his novel Absalom, Absalom!—a book that became integral in his achievement of the Nobel Prize. Laughing Boy is now a forgotten, second-rate novel while Faulkner and his works grew in prominence. Perhaps the Pulitzer committee sought to atone for their oversights by awarding Faulkner not one, but two Pulitzers—both for lesser works. He won in 1955 for his novel A Fable and in 1963 for his final book, The Reivers.

5. Thomas Pynchon

In 1974, scandal erupted after the Pulitzer board withheld the prize for fiction. The jury had voted unanimously for Thomas Pynchon’s novel Gravity’s Rainbow, but the board vetoed their recommendation calling the novel “obscene,” “overwritten,” “turgid,” and “unreadable.” The jury expressed dismay when they learned of the book’s rejection and protested the board’s decision but to no avail. Gravity’s Rainbow was indeed lengthy and written in a complex, postmodern style, making it a difficult book to describe.

Richard Locke in The New York Times Book Review wrote,"Gravity's Rainbow is bonecrushingly dense, compulsively elaborate, silly, obscene, funny, tragic, pastoral, historical, philosophical, poetic, grindingly dull, inspired, horrific, cold, bloated, beached and blasted.” It went on to win the National Book Award (jointly with Isaac Bashevis Singer’s A Crown of Feathers) and has since enjoyed critical acclaim. TIME magazine has named it one of the “All-Time 100 Greatest Novels.”