"Like shoemakers and tailors turning out more second-generation shoemakers and tailors, my father, Louis Ginsberg, the poet, had poets." –Allen Ginsberg

Artists and writers are sometimes thought of as being inherently rebellious—taking on low-paying professions and questionable lifestyles that inspire dread in the minds of their parents. But when your father is already a poet, just how rebellious can you be by comparison? If we ask Allen Ginsberg, the answer is obviously “very.”

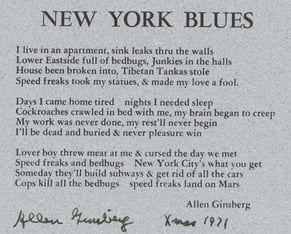

Ginsberg, who was one of the most important writers of the Beat Generation (right alongside Jack Kerouac and William S. Burroughs), earned his lasting place in the postwar canon for poems like 'Howl' (1956) and 'Kaddish' (1961) that tested the bounds of subject matter and formal possibilities previously thought unacceptable in poetry. Meanwhile, those same boundaries (from the notion that poetry should be metered to disagreement over what constituted an appropriate poetical topic) were being studiously upheld by Ginsberg’s own father, Louis Ginsberg.

Ginsberg, who was one of the most important writers of the Beat Generation (right alongside Jack Kerouac and William S. Burroughs), earned his lasting place in the postwar canon for poems like 'Howl' (1956) and 'Kaddish' (1961) that tested the bounds of subject matter and formal possibilities previously thought unacceptable in poetry. Meanwhile, those same boundaries (from the notion that poetry should be metered to disagreement over what constituted an appropriate poetical topic) were being studiously upheld by Ginsberg’s own father, Louis Ginsberg.

Though Louis Ginsberg is largely remembered as a footnote to his son’s legacy today, he was a successful, frequently anthologized poet in his own right—and his poetry could not have been more different from his son’s poetry. He was slavishly devoted to traditional meters and rhyme schemes, publishing quiet, pun-filled poems on such evergreen topics as stone buildings and fog. Hardly the free-verse anarchy dwelling on mental institutions and erotic vegetables for which Allen would be remembered.

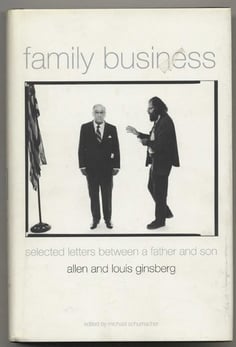

If the difference in their two poetical modes is profound, it’s because it was underpinned by a philosophical difference that extended far beyond poetry. In the letters that the pair exchanged throughout their lives (which can be glimpsed in 2001's Family Business: Selected Letters between a Father and Son, a collection that paints a moving portrait of the pair through their amazingly erudite correspondence), they frequently debated not just the right way to compose a poem, but the very basis of societal morality; Allen thought socially acceptable behavior was arbitrary and ‘rationalized’, while Louis believed that even if social norms were rationalizations, they were productive ones, whereas the rationalizations made by the insane were unproductive and even harmful. The upshot of this particular disagreement (which led not just to multiple letters to Allen but also a letter to famed literary critic Lionel Trilling, who was Allen’s professor at Columbia) was that Allen should stop cavorting with drug addicts and vagrants, should button his shirt up properly, and should stop hanging around with that shifty Burroughs fellow.

If the difference in their two poetical modes is profound, it’s because it was underpinned by a philosophical difference that extended far beyond poetry. In the letters that the pair exchanged throughout their lives (which can be glimpsed in 2001's Family Business: Selected Letters between a Father and Son, a collection that paints a moving portrait of the pair through their amazingly erudite correspondence), they frequently debated not just the right way to compose a poem, but the very basis of societal morality; Allen thought socially acceptable behavior was arbitrary and ‘rationalized’, while Louis believed that even if social norms were rationalizations, they were productive ones, whereas the rationalizations made by the insane were unproductive and even harmful. The upshot of this particular disagreement (which led not just to multiple letters to Allen but also a letter to famed literary critic Lionel Trilling, who was Allen’s professor at Columbia) was that Allen should stop cavorting with drug addicts and vagrants, should button his shirt up properly, and should stop hanging around with that shifty Burroughs fellow.

While the letters in Family Business show a frequently contentious dialog between the two writers—who failed to see eye-to-eye on communism, the Vietnam War, and other controversial issues of the era—they also show a relationship underpinned by real love and admiration. And, in fact, the two would sometimes give readings together (and, separately anyway, the two sometimes gave readings with Eugene Brooks Ginsberg, Allen’s older brother). The events proved to be studies in contrast, with the elder Ginsberg donning a suit and tie and calmly orating a few poems, followed by Allen taking the podium bare-chested, chanting with bells and hand cymbals. Because even when your father is a poet, it doesn’t hurt to rebel a little.