“No man but a blockhead ever wrote,” said Samuel Johnson, “except for money.” Even this humorous thought ignores the central reality of literary economics: that writing for money is very hard. At least, that is, if you want to live comfortably. This bare reality is in part why authors have for thousands of years supplemented their income and professional life with the profession of teaching.

For a writer today, the gravity of their profession leans so heavily toward teaching that writers who have never drafted a syllabus are something of an oddity. George Saunders teaches. Zadie Smith teaches. As does Marilynne Robinson, Robert Coover, Toni Morrison, Paul Muldoon, and Joyce Carol Oates. Any author over the age of forty who has mortgages and families in mind must think about the halls of academia to make ends meet. Jonathan Franzen is now successful enough to not worry, but he is an exception. As is Cormac McCarthy, who before success preferred to tolerate poverty than even make a paid appearance at a college. Michael Chabon has mostly avoided the obligation of keeping collegiate office hours, but this is in part because he has chosen the other supplemental career of a living author: show business.

For a writer today, the gravity of their profession leans so heavily toward teaching that writers who have never drafted a syllabus are something of an oddity. George Saunders teaches. Zadie Smith teaches. As does Marilynne Robinson, Robert Coover, Toni Morrison, Paul Muldoon, and Joyce Carol Oates. Any author over the age of forty who has mortgages and families in mind must think about the halls of academia to make ends meet. Jonathan Franzen is now successful enough to not worry, but he is an exception. As is Cormac McCarthy, who before success preferred to tolerate poverty than even make a paid appearance at a college. Michael Chabon has mostly avoided the obligation of keeping collegiate office hours, but this is in part because he has chosen the other supplemental career of a living author: show business.

The author-teacher who we see today is but the culmination of a long tradition of writers who help bring up the next generation of talent and wisdom. Here are a few of the notable examples of this staple figure of a healthy literary culture.

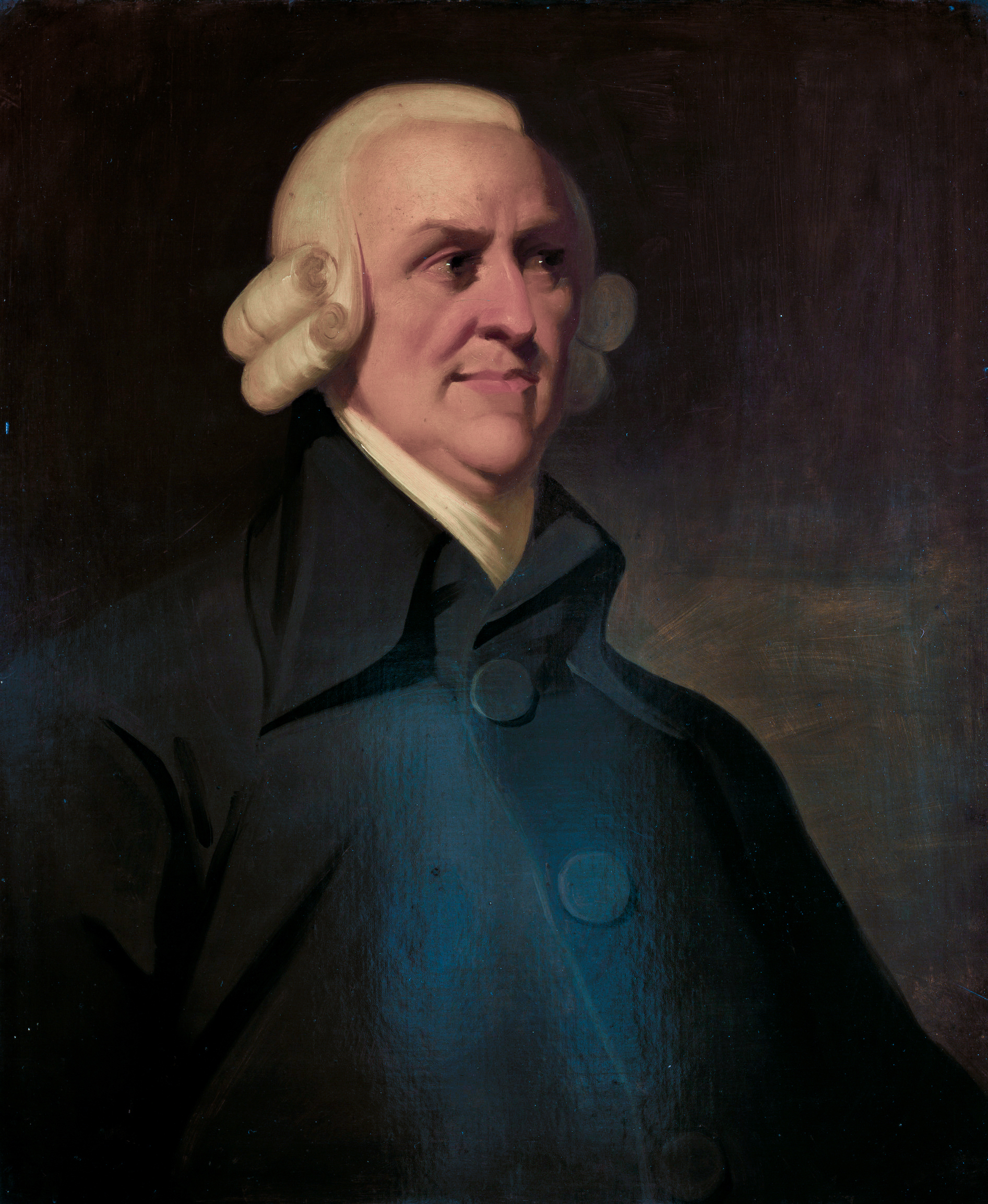

Adam Smith

Smith began lecturing in Edinburgh in his 20s, discussing issues of logic and art. In a few years, he began meditating on issues of liberty, wealth, and economics, and was granted a professorship at the University of Glasgow in 1752. Some of his lectures led to his book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, a now lesser-known work for which he became immensely famous. Before traveling as a tutor and dedicating more time to writing, he worked as an academic for 13 years, which he described as "by far the most useful and therefore by far the happiest and most honorable period of my life.”

John Ruskin

John Ruskin

Ruskin was appointed the inaugural Slade Professor of Fine Art at Oxford in 1869. The ever-curious writer, he not only wrote about politics, art, and architecture, but took to immersing himself in the topics he dedicated his philosophy to. His exquisite writing and vision, alongside fellow teacher Walter Pater, captivated a generation of British artists. But Ruskin’s teaching methods deserve special attention, as he believed not merely in writing and lecturing to seated students, but in providing a full pedagogical experience that involved physical and helpful work. His most talked about practice as an Oxford professor was to take his students out to dig and pave roads, moving earth and breaking rocks. “My chief object,” he wrote, “is to allow my pupils to feel the pleasure of useful muscular work.” Among his students engaged in the "digging scheme," who was also inspired by his thought and philosophy was a young Irishman named Oscar Wilde.

Wallace Stegner

Pulitzer Prize winner Wallace Stegner graduated from Iowa, soon to become known as the prestigious Iowa Writers’ Workshop. He then went on to teaching at the University of Wisconsin, Harvard, and Stanford, forging, as writer David Gessner described, “the prototype of the tenured writer.” Among his students he counted Wendell Berry, Ken Kesey, Sandra Day O’Connor, Edward Abbey, and more. The last twenty years of life after he retired were defined by a belated burst of creativity, where he published Crossing to Safety and Angle of Repose. Though the extra time was helpful to Stegner, he kept a productive output even in his teaching years. "That's what summers are for," as he liked to say.