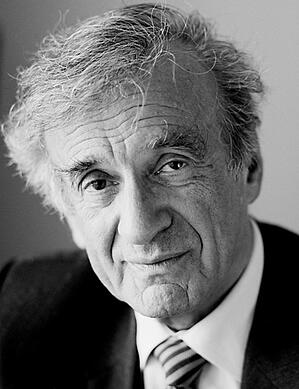

In 1978, a four part miniseries called Holocaust aired on NBC. It featured Meryl Streep as a cast member, and it portrayed all of the horrors that we have since come to expect from depictions of the Holocaust (to enumerate them would, perhaps, defeat the purpose). Though it was one of the earliest examples of this particular historical atrocity being adapted for prime time, in the ensuing decades it undoubtedly blurred together in the minds of its viewers with similar media like Schindler’s List (1993) and Sophie’s Choice (1982). Though the miniseries, which was ostensibly fictionalized from true events, would garner critical acclaim, Elie Wiesel, who remained one of the world’s foremost chroniclers of the Shoah until his death two years ago, hated it.

In a contemporary review for the New York Times, Night (1956) author Wiesel called the production “untrue and offensive.” Though he admitted that many of the facts had been correct, he resented the idea of one of the worst horrors in human history being turned into a melodrama. And this was not just a matter of taste. He elaborated in the same piece to say, “I am appalled by the thought that one day the Holocaust will be measured and judged in part by the NBC TV production bearing its name.” His point is bolstered in the next moment, in which he quotes from National Council of Churches’ study guide on the show: “‘Holocaust’ may come to be known as the definitive film on the Holocaust in terms of meticulous accuracy, totality of material presented, and its use of carefully selected archival footage...”

Later in that same paragraph, the Nobel Peace Prize laureate Wiesel couches his displeasure in clear terms: “The witness feels here dutybound to declare: What you have seen on the screen is not what happened there. You may think you know now how the victims lived and died, but you do not. Auschwitz cannot be explained nor can it he visualized.”

Looking backwards or forwards, it’s easy to envision Wiesel’s fear coming to pass; as the last remaining Holocaust survivors die out, their first-hand accounts are always in danger of being supplanted by the visual signs of the Holocaust that have been disseminated by Hollywood. And while Hollywood’s various depictions (including Holocaust) certainly have helped to spread information about the acts committed by the Nazis, one has to wonder (as Wiesel does) if it isn’t also easier to ignore, to explain away, and to distrust something that reaches us primarily through a medium as heavily codified and aestheticized as television.

In another Times piece published more than a decade later, Wiesel doubled down on his view of Holocaust media. He quotes Wittgenstein (“whereof one cannot speak, one must not speak,”), and reiterates his earlier objections: “Auschwitz is something else, always something else. It is a universe outside the universe, a creation that exists parallel to creation…it defeated art, because just as no one could imagine Auschwitz before Auschwitz, no one can now retell Auschwitz after Auschwitz.” Later, he rattles off a list of Holocaust representations that fail to meet his standard of reverence (and offhandedly mentions a few that do, like 1978's War and Remembrance, the Herman Wouk book, emphatically not the movie), before concluding that it’s an insult to victims and survivors alike to represent these horrors on screen.

Reading and thinking through the idea that Auschwitz is fundamentally impossible to represent, the question that arises is this: where does that leave Elie Wiesel’s project as a writer? Of course, Wiesel was himself a survivor with a first-hand account to relate (though novels like 1961 Dawn sometimes fictionalize that account), and many of the prolific author’s 57 books are not about the Holocaust itself (1997's Twilight, for instance, follows a Shoah survivor’s later life as a psychologist in America), but that doesn’t really change the fact that Wiesel’s Night, for instance, tries to tell a story that even he believes is fundamentally un-tellable. Of course, the world is a much richer place for his having told his story, and most of us would be hard pressed to imagine how much flimsier our understanding of man’s capacity for moral abdication would be without it. Whether Wiesel likes his own books is foolish to speculate upon, but there are pieces of Holocaust media he approves of—do they somehow skirt around the problem of the unutterable? Or is there a separate ethical layer to how we even attempt to approach a problem that we know can’t be solved.

For something resembling an answer, we might turn to one of Wiesel’s quotes about the act of writing: “I’d... say to a young writer, if you can choose not to write, don’t. Nothing is as painful. From the outside, people think it’s good; it’s easy; it’s romantic. Not at all. It’s much easier not to write than to write. Except if you are a writer. Then you have no choice.” Taken in combination with his thoughts on Holocaust the miniseries, we get a portrait of Wiesel that’s slightly different from the popular imagination. Yes, Wiesel stands as a voice for peace and against genocide, but he also appears as a crusader doomed to failure. In writing he’s like Sisyphus, making the same journey over and over again in the most strenuous and unpleasant way possible, climbing towards a destination that can never be reached. It would be easier not to do so, not to try and fail to express the inexpressible, but he can’t. Neither could Primo Levi. Perhaps neither could the producers of Holocaust. All are doomed to failure—so what does it matter how the art turns out? To paraphrase from The Lion in Winter (1968), when the failure is all that’s left, it matters a great deal.