“That’s not writing, that’s typing”

-Truman Capote on Jack Kerouac’s On the Road (1957)

Writers and readers alike are taught to be dubious of first drafts. “The first draft of anything,” Ernest Hemingway said, “is sh*t.” By that same reflex, many seem to find themselves wary of anything written too quickly. Detractors of National Novel Writing Month tend to express their disapproval by way of this wariness. They intimate, or sometimes say outright, that nothing of value could possibly be written that quickly.

It’s likely that many of these detractors already do not like Jack Kerouac. Kerouac, of course, is famous for having written his iconic road trip novel On the Road over the course of a mere three weeks in 1951, allegedly implementing a 120 foot long continuous roll of paper in order to maximally expedite his simultaneous typing and composition. Though Kerouac’s work was hugely influential, it was met with as much derision as praise, and many are quick to blame his practice of “spontaneous prose” for his perceived failings as a writer. Though Kerouac feels the brunt of the backlash from those who decry his lightning-fast writing (whether on the merits of the method or the writing), there are a number of writers and books to which the concept of “spontaneous prose” may be applied, some of them more surprising than others. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, for instance, wrote his classic Sherlock Holmes novel A Study in Scarlet (1887) during a span of only three weeks. Conan Doyle’s style might be said to be quite the opposite of Kerouac’s—Apollo to the Beat Writer’s Dionysus.

It’s likely that many of these detractors already do not like Jack Kerouac. Kerouac, of course, is famous for having written his iconic road trip novel On the Road over the course of a mere three weeks in 1951, allegedly implementing a 120 foot long continuous roll of paper in order to maximally expedite his simultaneous typing and composition. Though Kerouac’s work was hugely influential, it was met with as much derision as praise, and many are quick to blame his practice of “spontaneous prose” for his perceived failings as a writer. Though Kerouac feels the brunt of the backlash from those who decry his lightning-fast writing (whether on the merits of the method or the writing), there are a number of writers and books to which the concept of “spontaneous prose” may be applied, some of them more surprising than others. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, for instance, wrote his classic Sherlock Holmes novel A Study in Scarlet (1887) during a span of only three weeks. Conan Doyle’s style might be said to be quite the opposite of Kerouac’s—Apollo to the Beat Writer’s Dionysus.

Moving toward those with even more unimpeachable literary statuses, we find that Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Gambler (1868) was written in less than a month, though the circumstances were somewhat extraordinary. In order to pay off the gambling debt on which the novel was based, the famous Russian novelist agreed to produce a novel before November 1, 1886—just a month after the date of the agreement—or he would cede publishing rights to his novel for the following nine years. For his part, William Faulkner earns an honorable mention on this list. His tour de force 1930 novel As I Lay Dying was composed between midnight and four AM over the course of six weeks and published largely unedited.

Though the list of “spontaneous prose” writers has already proved long and wide-reaching, it may yet surprise some that Kazuo Ishiguro, who is widely considered to be one the most important British novelists of the past fifty years, wrote his classic novel The Remains of the Day (1989) in a span of just four weeks. If this, more than the others listed above, is a surprise, it may be because the novel—which follows old-world English butler Stevens in his attempt to cope with the postwar decay of the aristocracy—is one that dwells significantly on poise and propriety. More than anything, it is difficult to imagine a character like Stevens, who is reserved and proper, an expert at being unobtrusive, being created in a Keruoac-esque fever of prose writing. Such a proper novel seems to warrant a proper method: a gentle course of writing and editing spread out over a span of years.

Though the list of “spontaneous prose” writers has already proved long and wide-reaching, it may yet surprise some that Kazuo Ishiguro, who is widely considered to be one the most important British novelists of the past fifty years, wrote his classic novel The Remains of the Day (1989) in a span of just four weeks. If this, more than the others listed above, is a surprise, it may be because the novel—which follows old-world English butler Stevens in his attempt to cope with the postwar decay of the aristocracy—is one that dwells significantly on poise and propriety. More than anything, it is difficult to imagine a character like Stevens, who is reserved and proper, an expert at being unobtrusive, being created in a Keruoac-esque fever of prose writing. Such a proper novel seems to warrant a proper method: a gentle course of writing and editing spread out over a span of years.

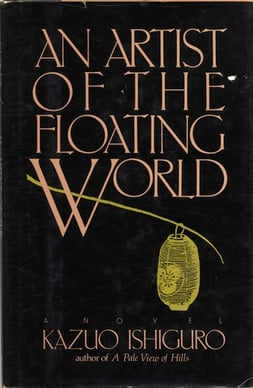

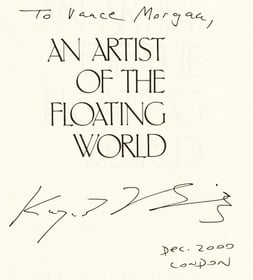

Nonetheless, it was precisely this wild and harried sort of “spontaneous prose” that led to the creation of the beloved novel. Though the writer produced his other works, like A Pale View of the Hills (1982) and An Artist of the Floating World (1986), in less dizzying time frames, he acquiesced to his wife, Lorna, who insisted that the work would only get underway in the manner of what they called “the crash,” during which Ishiguro would write 9 in the morning to 10:30 at night for four weeks. While Ishiguro had expected to encounter diminishing returns writing for so many hours, he ultimately found that the strategy suited him. And who could possibly argue with the results?

Though Ishiguro found great success with his ‘crash,’ he did note later on that he had done a significant amount of research before he embarked on it. He had been pondering the form of the novel for some time, and had read the biographies of a few English butlers in preparation. Does this diminish the effect of his “spontaneous prose,” or enhance it? For comparison, it’s worth noting that while Jack Kerouac’s On the Road took mere weeks to write, the autobiographical material on which he based had been given life in his own actions and thoughts over the course of the years that preceded it. These novels may, on the surface, appear to take less than a month, but there is a sense in which each book has taken the author’s entire life to create.