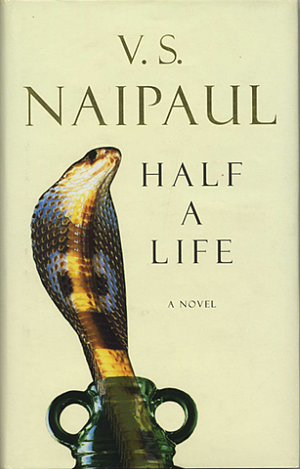

Writers are often meticulous and private people. Thus, the creation of authorized biographies can be a contentious matter. Some authors, like Nobel Laureate V.S. Naipaul, allowed a biographer into their home and shared personal information only to find that the resulting biography presented a person foreign to themselves. Although the biographer has a greater duty to his work than to his subject, one can understand why many authors feel betrayed at the end of the process. This article will catalog a few bitter episodes between authors and their biographers including V.S. Naipaul, William S. Burroughs, and Vladimir Nabokov.

V.S. Naipaul

As reported in a New Yorker article by author Teju Cole, V.S. Naipaul confessed that he was displeased with his authorized biography: Patrick French's The World Is What It Is. This portrait of the Nobel Prize-winning writer is often unflattering, presenting Naipaul as a vain and petty man. "One gives away so much in trust," says Naipaul, "One expects a certain discretion. It's painful, it's painful. But that's quite all right. Others will be written. The record will be corrected."

Unfortunately for Naipaul, French's biography was well-received, winning the National Book Critics Circle Award in 2008. It remains the only authorized biography of Naipaul to date

Teju Cole's article recounts a posh literary night in a penthouse on the Upper East Side and his conversations with Naipaul. Indeed, Naipaul encouraged him to write the article after learning that he had upset Cole's expectations - Cole had not found Naipaul "surly" as he had anticipated. Naipaul perhaps intended the article as a counterbalance to the unsettling accounts made in Naipaul's biography. But the article illustrates a more neutral portrait. Naipaul is contemplative, intelligent, and of course, a superb and respected writer. But his past is marked by considerable improprieties.

Naipaul carries with him accusations of misogyny, from his personal romantic history to his comments on the capacities of female writers. The Nigerian-American Cole points out that the author's treatment of African culture at times ventures into insensitivity. What emerges from frequent accounts of Naipaul is a man who is undeniably intelligent and talented, in addition to one who is difficult and sometimes offensive. It appears, in reading such accounts, that the two different qualities are not incommensurate in a single, gifted author.

William S. Burroughs

"It's awful," said William S. Burroughs about his biography, Literary Outlaw. He took issue even with the title, insisting that he was never in significant trouble with the law. However, it is fair to wonder, what portrait would satisfy Burroughs, this gun-loving, heroin-addicted, writer who accidentally killed his second wife?

Unlike Patrick French's biography of Naipaul, Ted Morgan's biography of Burroughs was not particularly beloved by critics. The biography characterized Burroughs in much the same way his legacy has—as an artist whose difficult books are frequently ignored in order to pay attention to the man who met celebrities and led a tumultuous life. Morgan was more concerned with the rock stars who confided in Burroughs (David Bowie, Mick Jagger, Patti Smith) than with critically assessing his life and work. Indeed, Morgan was not able to keep up with the ramblings of Burroughs during interviews. In one point of the biography, Burroughs quotes lines from a poem, but Morgan mistakenly attributed the lines to his subject.

Burroughs did have one demand for Morgan while writing the biography: "Don't pull a Truman on me." This was in reference to In Cold Blood, in which Burroughs blamed Truman Capote for not intervening in the killers' executions so that he could have a death scene. Even this demand was not exactly kept, as Morgan republished Literary Outlaw in 2012 to include the demise of the controversial author.

Vladimir Nabokov

It is not surprising that Vladimir Nabokov, one of recent literature's most fastidious readers, did not like his biography, Nabokov: His Life In Part. Nabokov allowed the biography but certainly not out of enthusiasm. He viewed a biography as an inevitability more than anything else, a mere process to begin sooner rather than later, for he believed that the first biography sets the tone for the following ones. Nabokov granted his biographer, Andrew Field, a series of interviews to write the book. No one can attest to what was truly said and done during these sessions, but Nabokov was certainly displeased upon reading the manuscript. In a letter he wrote:

It is not surprising that Vladimir Nabokov, one of recent literature's most fastidious readers, did not like his biography, Nabokov: His Life In Part. Nabokov allowed the biography but certainly not out of enthusiasm. He viewed a biography as an inevitability more than anything else, a mere process to begin sooner rather than later, for he believed that the first biography sets the tone for the following ones. Nabokov granted his biographer, Andrew Field, a series of interviews to write the book. No one can attest to what was truly said and done during these sessions, but Nabokov was certainly displeased upon reading the manuscript. In a letter he wrote:

If Field insists on telling the "history of bastardy and buggery" inherent in the Nabokov family, as well as publishing bits of my working notes toward a novel, and distorting information I gave him in idiotic ways (by asking strangers to check details of incidents that I alone could know), then I shall do everything to stop him in his stride, besides composing for a sympathizing periodical a special article about his dishonest behaviour and blunders.

Indeed, Nabokov tried to suppress the biography through litigation, but did not succeed. Some have speculated why such discrepancy between Nabokov and Field had occurred. Nabokov, ever conscious of personal persona and perception, was possibly a severe authoritarian, aiming to dictate much of the biography, including its title. It is rumored that during the interview process, Field presented Nabokov with one of his novels, which Nabokov incisively derided and criticized. This would explain Field's vindictive altering of Nabokov's conversation, in a grand attempt to subvert the imperious writer's demands.

Nabokov, it is widely recognized, used this ordeal as inspiration for his final work of fiction, Look at the Harlequins!. It is a fictional autobiography whose protagonist in many ways resembles the book's author. Nabokov has always blurred the fictional and factual. His memoir, Speak, Memory, is alleged to contain fictitious elements, such as his claim to synesthesia. And some of his fiction, like his most genius work, Pale Fire, is replete with metafictional insight and exploration. One critic, in an essay entitled "Nabokov: His Life Is Art," maintained that Andrew Field does not really exist, and argues that the only way the biography can be explained is if it was written by Nabokov himself.