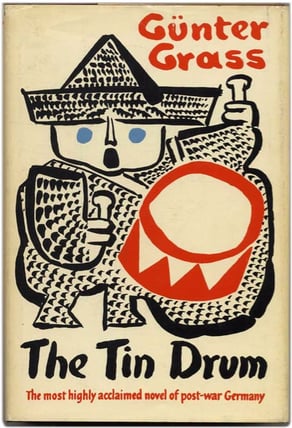

The great German novelist, Günter Grass, has died at age 87. He won the 1999 Nobel Prize in Literature for his "frolicsome black fables [that] portray the forgotten face of history" and the Nobel Academy named him the "predecessor" of "García Márquez, Rushdie, Gordimer, Lobo Antunes and Kenzaburo Oe." Although his landmark 1959 novel, The Tin Drum, was initially rejected by his countrymen, it became an international success and launched his career. Grass became known as the conscience of Germany--a status that later became questioned when he disclosed his involvement during World War II.

With The Tin Drum, Grass inspired many with his ability to write with a full range of emotions and an outpouring of language. The reader experiences tremendous guilt and relief in The Tin Drum and the entire Danzig trilogy which continues with Cat and Mouse (1961) and is finished with Dog Years (1963). Indeed, The Tin Drum was called a new beginning for German literature after so many decades of destruction.

With The Tin Drum, Grass inspired many with his ability to write with a full range of emotions and an outpouring of language. The reader experiences tremendous guilt and relief in The Tin Drum and the entire Danzig trilogy which continues with Cat and Mouse (1961) and is finished with Dog Years (1963). Indeed, The Tin Drum was called a new beginning for German literature after so many decades of destruction.

Both as a writer and as a public figure, Grass loudly decried German actions during World War II. For example, he strongly opposed reunification after the fall of the Berlin Wall, comparing it to Hitler's "annexation" of Austria. He believed that the division of Germany was both a just punishment for the Holocaust and way to protect the country from itself.

Yet Grass has become a controversial figure since he revealed his role in the Waffen-SS in 2006. He was a very young man during the war years and many had assumed that his involvement with the Nazi war machine did not go beyond youth organization membership. However, it has been revealed that as a boy he attempted to join the submarine corps at 15, and was turned away. Later he was drafted into the Waffen-SS at 17. There, Grass fought in a Panzer division before becoming a prisoner of war.

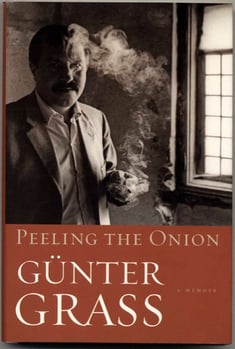

Many complain that as a writer who trumpets the moral compass of man and nations alike, it is hypocritical to have fought with for the same Nazi groups he blasts in his works. Others, such as contemporary Jewish author, Ivan Nagel, noted that it took him 55 years to be able to talk about his trials as one of the persecuted, and he understands how it may have taken Grass 60 years to talk about his shame and his disgrace in his autobiography, Peeling the Onion.

Many complain that as a writer who trumpets the moral compass of man and nations alike, it is hypocritical to have fought with for the same Nazi groups he blasts in his works. Others, such as contemporary Jewish author, Ivan Nagel, noted that it took him 55 years to be able to talk about his trials as one of the persecuted, and he understands how it may have taken Grass 60 years to talk about his shame and his disgrace in his autobiography, Peeling the Onion.

Grass spoke of his awakening to the true horrors of the war. When he was 17, "the war was over, and I was in an American prison camp — a prisoner of war. And slowly, slowly I discovered what really has happened. And [in] the beginning I didn't believe — I thought it was propaganda what they were telling us. It's not possible the German people has done this."

But then he heard the Nuremberg trials. "I listened to the radio, and I heard my former Youth Leader ... And he said yes, it's true. It's terrible. But from this moment on, it was clear for me what has happened. And this knowledge never left me."

"I had to write about my time, what has happened to my generation, what has happened to my country," he said. "I was confronted. There was no way out."