When you first enter into the world of rare books, you might think you’ve encountered a new language in some ways. Rare booksellers, collectors, and archivists use many words and phrases that can be difficult to parse. In addition, there are simply a lot of those words and phrases to learn. Some refer to the condition of the book, others refer to the way the book was made or to its style and aesthetic, and yet others still reference information about the book’s publication or ownership. And in many cases, there are multiple terms in use that refer to the same thing! We couldn’t possibly provide you with every word or phrase you might see used in a description of a rare book, but we can certainly get you started. We’ve separated some of those words and phrases into distinct categories to help you get acquainted with the language of the rare book trade.

Rare book dealers, buyers, and collectors rely on a wide variety of words and phrases to describe the condition of a book or object. First, there are terms used to describe the condition the book is in—usually ranging from “as new” or “fine” down to “poor” or “reading copy” or “binding copy.” We want to tell you a little bit about these terms to start. The best possible condition in which you can find a rare book is “as new” condition, but this kind of condition in itself is relatively rare. For most booksellers, “as new” means the book looks just like it did when it was originally published and sold. For any rare books that are older, you’re unlikely to find a copy in “as new” condition. Indeed, for most older rare books, the best condition you’ll see listed is “fine.” When a book is in “fine” condition, it has some signs of handling, but there are absolutely no imperfections present. For example, the book will not have any tears or marks, and will generally look like a book in perfect condition aside from the fact that it has been handled or opened.

Books that are in “very good” condition typically might have some very minor imperfections, such as a small mark, but the dust jacket will not have any tears, the pages of the book will not have any tears, and any defects will be limited. Once a rare book is described as being in “good” condition, it may have some clear imperfections such as a small tear or stain, and it may look worn, but the book will be intact and will not have major issues. Then, a book that is listed as being in only “fair” condition likely means that the book has some obvious imperfections. For example, it might be missing its dust jacket or the dust jacket might be damaged, the binding may be quite loose, and even endpapers could be lacking. (You might be wondering: what’s an endpaper? Don’t worry—we’ll get there in just a little while.)

Now for the categories that suggest that book really has some problems in terms of its condition. A book that is listed as being in “poor” condition likely will have significant aesthetic imperfections like tears or stains, missing portions, loose bindings, and no dust jacket (if the book initially came with one). You might also see condition notes of “reading copy” or “binding copy.” These are not necessarily worse than a book in “poor” condition, but they have major defects. The term “reading copy” is typically used to describe a book that is in fair or poor condition, but that has no defects to any of the text pages—i.e., you can still read it perfectly. A book described as a “binding copy” is typically one that is in fair or poor condition because the binding is so damaged, but all of the pages (including plates or maps, for example) still exist. For collectors, there’d need to be a pretty good reason to buy a book that is in “fair” or worse condition. For most collectors, buying a book in “fair” or worse condition means that there’s something so special about the book that it makes sense to add it to the collection.

Those are just the terms that people in the rare book world use to classify the condition of a book or object. There are also some terms that concern condition. Most often, you might see a reference to “foxing” in the description of a book that’s for sale. It probably doesn’t mean what you think it means. It’s a term that’s typically used to refer to spots of discoloration on a book that are often a dark brownish red color, but they can also appear in other colors. It’s important to be clear that foxing does not refer to spots caused by mold or to marks caused by water damage. You might also see reference to “yellowing” or “yellowed” pages. Typically, a rare bookseller will use this term to refer to damage resulting from sunlight and fading, color changes as a result of dust, or fading caused by paper acids. Some booksellers will use the term “sunned” to describe this damage. You might also see reference to a “dampstain,” which refers to damage caused by a liquid (water or otherwise). Booksellers can also use the term “browning” to describe discoloration that’s often due to age or decomposition of the paper, and “bumping” to describe slight damage to the corners of a book (often caused by poor handling or shelving).

Beyond staining to the book, you might see a reference to “fraying” in a bookseller’s ad or at auction. This term describes damage to the cloth covering the book boards, sometimes resulting in the book. You could also see a bookseller reference a “chipped” dust jacket. This term means what you’d probably guess: little pieces of the dust jacket have chipped off. Sometimes the term is also used to refer to book pages, or even to the book binding. And finally, you might read that a book is “dog-eared,” which means that someone has folded down one or more of the pages (often while reader as a place keeper), with the fold resembling a dog’s ear.

Physicality, Format, and Style of the Object

Physicality, Format, and Style of the Object

Physical Aspects of the Book

When it comes to the format and aesthetics of rare books, there are many different terms that are used to describe the physicality of the book, its style, and the way it was crafted. We’re going to start with the physicality of the object. Let’s begin with the cover of a book. You might see a reference to “boards,” which is a term that’s sued to describe the covers (both front and back) of a hardbound book. What this term means is that the book’s cover was made with—typically—bookboard that has been covered in cloth prior to being bound. Differently, the term “wraps” is used to describe the paper cover on a paperback book. The “spine” is the part of the book the cover the binding of the pages inside and it’s sometimes described as the “back” of the book. The “tail” is the heel or bottom of the spine. The “hinge” is the part of the book adjacent to the spine that allows a handler to open and close the book.

When it comes to terms that describe the physical aspects of a rare book, you’ve probably seen references to the “leaves” or a “leaf.” What’s a leaf, you’d like to know? A “leaf” is a piece of paper, put most simply, or a page in a book. The front side of the leaf is typically described as the “recto” while the back side of the leaf is usually described as the “verso.” Sometimes you’ll see “obverse” substituted for “recto,” and “reverse” substituted for “verso.” Speaking of leaves, how about the term “fly-leaf”? This is a term that’s used to describe the blank page (the “leaf”) that appears in a book just after the front endpapers or just before the back endpapers. Oh yes, endpapers: also known as “endleaves,” the endpapers are added after the book has been printed and are usually pasted down so that they connect the inside of the cover (either front or back), and the first leaf or the verso of the last leaf. This sounds a bit confusing, but you probably know what these are—as soon as you open a hardcover book, there’s often decorative (and sometimes handmade paper) covering what you see when you open the book. That’s an endpaper, and the same thing appears if you open the back cover of the book.

When it comes to terms that describe the physical aspects of a rare book, you’ve probably seen references to the “leaves” or a “leaf.” What’s a leaf, you’d like to know? A “leaf” is a piece of paper, put most simply, or a page in a book. The front side of the leaf is typically described as the “recto” while the back side of the leaf is usually described as the “verso.” Sometimes you’ll see “obverse” substituted for “recto,” and “reverse” substituted for “verso.” Speaking of leaves, how about the term “fly-leaf”? This is a term that’s used to describe the blank page (the “leaf”) that appears in a book just after the front endpapers or just before the back endpapers. Oh yes, endpapers: also known as “endleaves,” the endpapers are added after the book has been printed and are usually pasted down so that they connect the inside of the cover (either front or back), and the first leaf or the verso of the last leaf. This sounds a bit confusing, but you probably know what these are—as soon as you open a hardcover book, there’s often decorative (and sometimes handmade paper) covering what you see when you open the book. That’s an endpaper, and the same thing appears if you open the back cover of the book.

How about rare book formats? You might see a reference to a “folio,” a “quarto” or “4to,” an “octavo” or “8vo,” and in some cases a “duodecimo” or “12mo” or “sextodecimo” or “16mo.” What do they mean? Generally speaking, when the word “folio” is used to describe the size of a book, the term means a book with sheets (or pieces of paper) that have been folded only once, producing a book that is larger than 13 inches. You’ll sometimes see this term abbreviated as “fo.” Depending upon the book, you might see larger folios described with the terms “elephant folio,” “atlas folio,” or “double elephant folio.” Yes, you’ve guessed it—the double elephant folio is extremely large and is a term that’s often used to describe folios that are larger than 50 inches high. When pages are folded only once as in a folio, the book is made up of groupings of two leaves or four pages. A “quarto” or “4to” is one of the most common sizes or formats for books. These two terms, which can be used interchangeably, refer to a book that has been created by folding a sheet two times so that you have four leaves.

Imagine you have a single piece of paper that you fold in half, and then you fold it in half again—a quarto or 4to is made up of groupings of these folded pieces sheets. Usually they’re around 12 inches in height, but the size is not determinative. Now onto the “octavo” or “8vo.” This is a term that describes a book that has been made by folding a sheet three separate times so that you have eight leaves. An octavo is made up of multiple groupings of these folded sheets. An octavo is usually about 9 or 10 inches in height, but again, the sheer size of the book is not determinative.

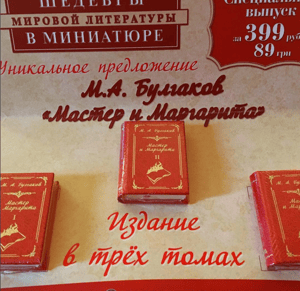

Now, believe it or not, there are rare and antiquarian books made up of sheets that have been folded even more times. These kinds of books are less common. A “duodecimo” or “12mo” is a book created by folding a sheet into 12 leaves, resulting in 24 book pages. These books are usually about 5” x 7” but the size can vary depending upon the original sheet. Finally, a “sextodecimo” or “16mo” is created by folding a sheet into 16 leaves, or 32 pages. We didn’t mention them above, but books can also get even smaller and can be created with even more folds of a single sheet. Beyond these terms, you might also see an “octodecimo” or “18mo,” a “tricesimo-secondo” or “32mo,” a “quadragesimo-octavo” or “48mo,” and a “sexagesimo-quarto” or “64mo.” By now, you probably understand how these terms work—they were to the number of leaves created by folding a single sheet. The latter descriptions are usually very small books, but they need not be—in theory, you could make one of these books with a very large sheet, resulting in a book that looks to be of average size. In reference to terms that describe size alone, booksellers usually use the term “miniature” to refer to books that are smaller than 2” x 1.5”.

Now, believe it or not, there are rare and antiquarian books made up of sheets that have been folded even more times. These kinds of books are less common. A “duodecimo” or “12mo” is a book created by folding a sheet into 12 leaves, resulting in 24 book pages. These books are usually about 5” x 7” but the size can vary depending upon the original sheet. Finally, a “sextodecimo” or “16mo” is created by folding a sheet into 16 leaves, or 32 pages. We didn’t mention them above, but books can also get even smaller and can be created with even more folds of a single sheet. Beyond these terms, you might also see an “octodecimo” or “18mo,” a “tricesimo-secondo” or “32mo,” a “quadragesimo-octavo” or “48mo,” and a “sexagesimo-quarto” or “64mo.” By now, you probably understand how these terms work—they were to the number of leaves created by folding a single sheet. The latter descriptions are usually very small books, but they need not be—in theory, you could make one of these books with a very large sheet, resulting in a book that looks to be of average size. In reference to terms that describe size alone, booksellers usually use the term “miniature” to refer to books that are smaller than 2” x 1.5”.

Now onto aesthetics and style. When it comes to rare book bindings, there are a lot of different styles. Some of the styles that are used currently to make books have been used for hundreds of years, while other binding styles are quite new and rely on contemporary technologies. In the present, “saddle stitching” refers to books that have been bound with staples, while a “perfect binding” refers to a book that has been bound with an adhesive. They’re not common in the rare book world, but “coil” or “spiral” bindings are those that have been bound with a spiral wire or piece of plastic by a machine (like a spiral-bound notebook). Some pieces of ephemera or artist’s books are bound with a “metal screw post” or “plastic screw post” binding. These are what they sound like—there’s a single post that goes through the leaves and binds them together, typically in one of the corners. There are a variety of Japanese bookbinding styles, with “stab binding” techniques used most commonly. With stab bindings, the outer edges of a book are literally stabbed and sewn in a particular pattern with embroidering or other threads.

Historically, in terms of bindings, you may see references to “calf” bindings, which are leather bindings using calf hide. There are many different types of calf bindings, including “diced” (where square or diamond designs are scored into the leather), “marbled” (where the leather has been stained so that it has a marbling effect), “mottled” (where the leather has been stained to produce more random designs than marbling), “paneled” (where there’s some sort of framing on the leather cover that’s typically made by leather tooling or gilt, and we’ll get to gilt shortly!), and Speckled (where the leather has been stained to intentionally have specks or spots). There are other examples of calf binding, too. “Morocco” bindings are another type of binding that have been used since the 1500s. They often have colorful dyes and are made of goatskin. Like calf bindings, there are many different types of Morocco bindings. You can have “crushed” Morocco bindings (where the leather has been flattened so that you cannot see the leather grain), “Levant” (large and refined), “Niger” (rubbed leather named for the region in West Africa where the style originated), and “straight grain” (a leather styled through moistening the skin). You might also read about “Cosway-style” bindings (which have portraits within the covers), “vellum” (one of the oldest bindings—used since medieval times—originally made from calfskin and now often made from lamb or goat), “Roan” (a sheepskin that is designed to look like a Morocco binding but is less elegant), “metallic” (bound with metals), or “jeweled” (bound with gemstones).

Now onto the paper inside the book. Many rare books have “deckle edges,” which is a term that describes book edges that look rough. Until the nineteenth century, nearly all books had deckle edges, while they are now a design choice. They are often untrimmed and may be described simply as “untrimmed” pages. However, you should be sure to distinguish between “untrimmed” and “uncut” pages—the latter refers to a book made up of a folded leaf that has not been cut. Accordingly, all of the pages of an “uncut” book cannot be opened. In many descriptions, this is referred to as an “unopened” book. When it comes to page styling and aesthetics, endpapers also tend to be styled significantly. Many, like we mentioned above, are from handmade papers, but endpapers can also be made up of silk and other exquisite fabrics, or other textiles. You might also see references to “glassine paper” in a description for a book. This is a particular kind of translucent paper that can be used as a dust jacket or as wraps, and can even contain printing.

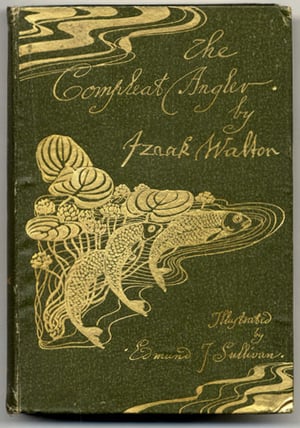

We previously mentioned gilt. Let’s spend a moment on gilt. In the rare book world, this term refers to the application of gold or a gold-like material onto a book. Sometimes gilt can be applied to the spine or the cover, and it’s often applied to the edges of the book. If you look at a book with gilting when the book is closed, it might appear as though you are holding a block of gold, bound by a cover. In the truest use, gilting is done with the application of gold leaf, which is a sheet of actual gold that has been hammered into a very thin sheet, or with gold powder. Gilting is done for aesthetic reasons, and it’s also done to help preserve the book from damage due to dust or moisture.

We previously mentioned gilt. Let’s spend a moment on gilt. In the rare book world, this term refers to the application of gold or a gold-like material onto a book. Sometimes gilt can be applied to the spine or the cover, and it’s often applied to the edges of the book. If you look at a book with gilting when the book is closed, it might appear as though you are holding a block of gold, bound by a cover. In the truest use, gilting is done with the application of gold leaf, which is a sheet of actual gold that has been hammered into a very thin sheet, or with gold powder. Gilting is done for aesthetic reasons, and it’s also done to help preserve the book from damage due to dust or moisture.

We didn’t come close to cover anywhere near the total number of terms that could be used to describe the physical aspects of a rare or collectible book or the ways in which books are made and styled, but we hope you have a good starting point based on the above information. Now, we want to turn to some of the terms that are used to describe publication and ownership.

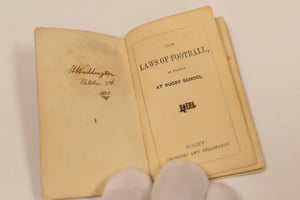

First, we’ll focus on all those different copies you might see referenced: “advance copy,” “association copy,” “dedication copy,” “inscribed copy,” “presentation copy,” and “signed copy.” That’s a lot of copies, but there’s some good news if you’re trying to learn these terms: they’re relatively easy to distinguish among once you know what they mean. Let’s start with the “advance copy.” This is a term that’s used to describe a book that’s printed before an official publication date. It usually is printed with a different cover or even in a different format, and it’s printed to send to reviewers, authors, and others to look at ahead of time. Advance copies are different from first editions (they are not a first edition), but they are often quite collectible. Now onto the “association copy,” which has been inscribed by the author to a friend, family member, or another important person to the author. You should note that an “association copy” is different from an “inscribed copy,” which is a book that has been inscribed by the author to the owner of the book (who may or may not be a person or significance). A “signed copy” means there’s no inscription, but the author signed the book. A “presentation copy” is similar to an “association copy” or an “inscribed copy” but are still distinct—presentation copies are those that have been given as a gift by the author to another person (with an inscription and signature from the author inside). Finally, a “dedication copy” is a book that has been inscribed by the author to the person to whom the book was dedicated. Dedication copies are especially rare, as are association copies and presentation copies. Certain inscribed copies can also be extremely valuable, especially when they are inscribed to significant figures.

The term “advance copy” brings us to the commonly used terms “galleys” and “first edition.” The term “galleys,” or a “galley proof,” is a term that is used to describe one of the first publications of the book that is typically used for in-publishing house purposes. It’s distinct from an advance copy in that it’s not printed with the intention of sending it out to readers. Instead, a galley proof will be printed before an “advance copy.” How about the elusive “first edition”? The term “first edition” is used to describe the first (ever) printing of a book by the first publisher. It is distinct from a “first impression” and a “first edition thus” and a “first trade edition.” When a publisher plans to have multiple printing runs of a book, it will distinguish the various “impressions” of the book, meaning the printing runs. A first edition, first impression is usually the most valuable book for collectors, although there are a number of exceptions. A “first edition thus” means it’s the first edition for that publisher, but it’s not the first edition of the book. And finally, a “first trade edition” refers to the first time a book has been printed with the intention of releasing it to a wide audience, or to the general public. Most first trade editions appeared beginning in the 1970s, and they all have ISBN numbers.

Whew—that’s a lot of information! Do you want to learn more? Or do you have a specific word or phrase you’re trying to understand when it comes to rare books and manuscripts? In the short term, you can check out a glossary of rare book terms. Yet you should also keep in mind that your rare book vocabulary will grow as you continue to collect and to learn.