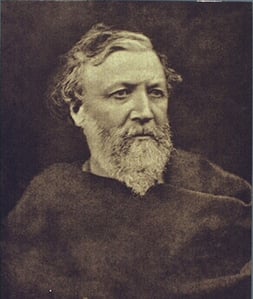

Today, Robert Browning is a firmly canonical author. His art draws a line between the Victorian literary tradition of psychological realism and the following tidal wave of modernism. His great talent is most apparent in his dramatic monologues, in which his poetry expertly illustrates the thoughts, motivations, and intellectual machinations of a character. Yet despite his posthumous fame, for a considerable portion of his life, Browning was overshadowed by his poetically gifted wife, Elizabeth Barrett.

Their relationship began when Browning wrote to Elizabeth as an admirer. She had just published a worthy collection of poetry and was celebrated in Britain. Browning wrote effusively to her. “I love your verses with all my heart, dear Miss Barrett,” he said in his first letter. Their correspondence led to a romantic relationship, kept secret from Elizabeth’s domineering father who would no doubt condemn Browning for merely wanting to marry up the social ladder. Browning adored the poetry of his more-famous paramour, and Elizabeth, six years his elder and sickly, was flattered by the love of her vigorous partner.

Their relationship began when Browning wrote to Elizabeth as an admirer. She had just published a worthy collection of poetry and was celebrated in Britain. Browning wrote effusively to her. “I love your verses with all my heart, dear Miss Barrett,” he said in his first letter. Their correspondence led to a romantic relationship, kept secret from Elizabeth’s domineering father who would no doubt condemn Browning for merely wanting to marry up the social ladder. Browning adored the poetry of his more-famous paramour, and Elizabeth, six years his elder and sickly, was flattered by the love of her vigorous partner.

Elizabeth Barrett was not only famous for her poetry, she was an impressive proponent of social justice. Her writings clearly reveal a strong feminism. In her famous work Aurora Leigh, the central relationship is not between Aurora and her innocuous suitor (whom she rejects twice), but rather her feminine companionship with the lower-class Marian. Elizabeth Barrett was bold in her insistence to set her poetry in her own age, not in the fixed, intransigent past as was conventional practice. Beyond the elevation of women, her social platforms extended to child labor and even overseas to the abolition of American slavery.

Some scholars blame Browning for stifling his wife’s creativity and vibrancy. Her writings and advocacy dwindle after the wedded pair moved to Italy. This, of course, ignores Elizabeth’s constant ill health (her reason for abandoning the English climate), and the laudanum habit she developed to cope with her pain. And indeed, Elizabeth published some of her best work, namely Sonnets from the Portuguese and Aurora Leigh, shortly after their marriage. Yet is there, in this great literary marriage, an act of parasitism on the part of Robert Browning?

Browning’s most famous work is a narrative poem called The Book of Rings. In it, he creates the character Pompilia whose aesthetic origins can be traced to the feminine heroes of his wife’s magisterial Aurora Leigh. Aurora Leigh had been called by John Ruskin the greatest long poem of the nineteenth century. We know from the very beginning that Browning was a devoted reader of his wife’s work, and it appears a borrower from it, as well. Some readers familiar with the pair might even locate a rivalry on his part—one in which a jealous Browning uses his work as battleground to elevate himself at his wife’s expense. Critic Nina Auerbach argues that his invention of Pompilia, both a plagiarization and bastardization of Elizabeth’s great characters, “may be Robert Browning’s ultimate victory over his celebrated wife.”

Browning’s most famous work is a narrative poem called The Book of Rings. In it, he creates the character Pompilia whose aesthetic origins can be traced to the feminine heroes of his wife’s magisterial Aurora Leigh. Aurora Leigh had been called by John Ruskin the greatest long poem of the nineteenth century. We know from the very beginning that Browning was a devoted reader of his wife’s work, and it appears a borrower from it, as well. Some readers familiar with the pair might even locate a rivalry on his part—one in which a jealous Browning uses his work as battleground to elevate himself at his wife’s expense. Critic Nina Auerbach argues that his invention of Pompilia, both a plagiarization and bastardization of Elizabeth’s great characters, “may be Robert Browning’s ultimate victory over his celebrated wife.”

Where Aurora Leigh is a learned and sophisticated speaker of herself, Pompilia is illiterate. Aurora and her friend Marian are affirmative women and speak brilliantly for themselves. Take for example Aurora’s strong, feminist address to her friend:

I am a woman of repute;

No fly-blow gossip ever specked my life;

My name is clean and open as this hand,

Whose glove there's not a man dares blab about

As if he had touched it freely:–here's my hand

To clasp your hand, my Marian, owned as pure!

As pure,–I'm a woman and a Leigh!

Compare this to a passage in The Book and the Ring in which Pompilia is characterized by a male character:

It was not given to Pompilia to know much

Speak much, to write a book, to know mankind,

Be memorized by who records my time.

Pompilia was an inexpressive woman in need of validation from (masculine) characters, and is forgotten unless she can be saved by the interpretations of others. Pompilia was created as a composite of Elizabeth Barrett’s noble pair of Aurora and Marian, and thereafter strips them of their exuberance. This act of appropriating his wife’s expression and diluting it is foreshadowed in one of Browning’s funerary writings on his wife,

Teach me, only teach, Love!

As I ought.

I will speak thy speech, Love.

Think thy thought.

He did speak her speeches, “but in muting them to a dying whisper among dramatic monologues," Auerbach writes, “he drained them of authority.” How conscious Browning was of the appropriation of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s work is anyone’s guess. What we do know is that Robert Browning has outshone his wife in posterity, but we are obliged to remember whose very talents his work was bolstered by.