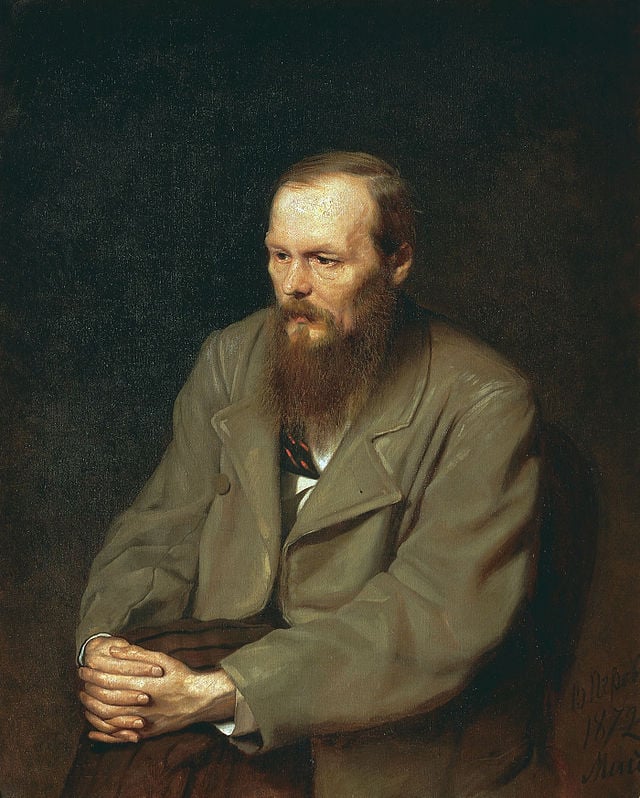

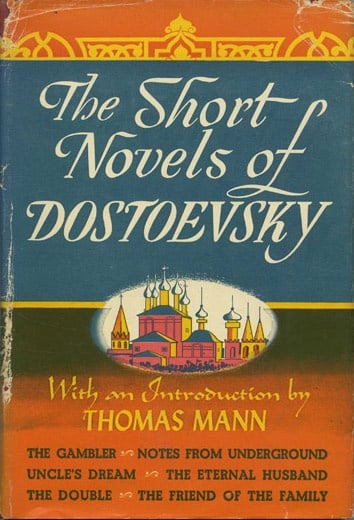

In spite of extremely stiff competition, Fyodor Dostoyevsky remains one of the most widely read and highly regarded Russian novelists of all time. His acclaimed novels, from The Brothers Karamazov (1880) to Crime and Punishment (1866) to Notes from Underground (1864), carved out a unique niche at the corner of psychological realism and existential philosophy. With the patina of great literature draped over these great works, however, we sometimes forget that these books were often strange, darkly funny, and oddly joyous—befitting, perhaps, the life of the man who penned them.

1. He wrote to pay off his gambling debts.

Dostoyevsky faced financial struggles throughout his life, due in no small part to what a modern psychologist would have deemed a debilitating gambling addiction. In one particular incident, he agreed to write a novel to pay off his debts, agreeing to a contract that would give his publisher that rights to all of Dostoyevsky’s previously published work for nine years if he failed to produce a novel by November 1 of that year.

Dostoyevsky faced financial struggles throughout his life, due in no small part to what a modern psychologist would have deemed a debilitating gambling addiction. In one particular incident, he agreed to write a novel to pay off his debts, agreeing to a contract that would give his publisher that rights to all of Dostoyevsky’s previously published work for nine years if he failed to produce a novel by November 1 of that year.

2. He wrote a novel in 26 days.

As a result of entering into the undeniably questionable contract above, Dostoyevsky was forced to set aside his work on what would become Crime and Punishment (which he knew he could not finish by the deadline) in order to churn out, as quickly as possible, another novel appropriately called The Gambler (1867). For those keeping score at home, that’s five days slower than Jack Kerouac’s writing of On the Road (1857).

3. His work inspired Ralph Ellison.

Dostoyevsky’s influence can hardly be quantified, and any existential author of the past century and half owes a debt to his writings. But in addition to helping to pave the way for the likes of Sartre and Camus, Dostoyevsky also had a huge, direct influence on Ralph Ellison. To wit, the narrator (and structure) of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man (1952) is directly modeled after Dostoyevsky’s Notes from Underground.

4. He was part of a mock execution.

After the publication and warm reception of his first novel at the age of 25, Dostoyevsky joined a liberal, atheist discussion group that was accused of conspiring against Tsar Nicolas I. Attempting to make exemplars of the group, the Tsar sentenced the lot of them to death by firing squad. Before the actual execution, however, it was apparently arranged that each convict would undergo a symbolic beheading, with a fake sword broken over each one’s head. This done, the firing squad prepared to shoot—but was called off at the very last second by an envoy from the Tsar conveying a stay of execution. The group of dissidents, Dostoyevsky included, were sentenced instead to hard labor in Siberia. Hard labor which did not go well for Dostoyevsky because…

After the publication and warm reception of his first novel at the age of 25, Dostoyevsky joined a liberal, atheist discussion group that was accused of conspiring against Tsar Nicolas I. Attempting to make exemplars of the group, the Tsar sentenced the lot of them to death by firing squad. Before the actual execution, however, it was apparently arranged that each convict would undergo a symbolic beheading, with a fake sword broken over each one’s head. This done, the firing squad prepared to shoot—but was called off at the very last second by an envoy from the Tsar conveying a stay of execution. The group of dissidents, Dostoyevsky included, were sentenced instead to hard labor in Siberia. Hard labor which did not go well for Dostoyevsky because…

5. He was epileptic.

As such, he was given to frequent seizures during his four years in the penal colony. The seizures had not been entirely unknown to Dostoyevsky at that point, and they would return later in his life as his health began to fail. His epilepsy did, however, seemingly influence the creation of his novel The Idiot (1869), which follows the doings of a Christ-like epileptic journeying through Russia.

6. Tsar Alexander II wanted him to tutor his children.

While Tsar Nicolas I obviously had, on the whole, a negative relationship with Dostoyevsky, the great writer’s eventual fame apparently made him much more palatable to the tsarist regime. In fact, Nicolas’ successor, Tsar Alexander II once ordered Dostoyevsky to give a reading at his palace, insisting afterwards that Dostoyevsky tutor the monarch’s sons—an appreciable improvement over the writer’s treatment at the hands of Nicolas I. Though, perhaps we shouldn’t be too shocked by Alexander’s comparative liberality, considering that it was he who finally emancipated Russia’s serfs.

7. Vladimir Nabokov hated him.

To be fair, Nabokov hated a lot of things: jazz, public pools, psychoanalysis, Thomas Mann, William Faulkner, etc. But Nabokov, arguably one of the greatest Russian novelists of all time (for certain definitions of “Russian”; his best works were certainly written in English after he moved to America), apparently also had a bone to pick with Dostoyevsky’s writing. He seemed to think of the writer's oeuvre as being petty and juvenile, summing up Crime and Punishment with an offhanded “Who cares?” Luckily, Nabokov’s assessment hasn’t done much damage to Dostoyevsky’s reputation in the long term.