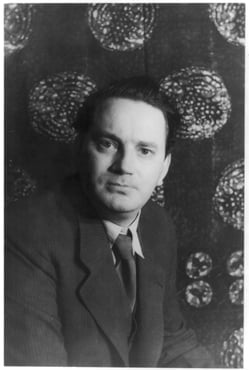

Thomas Clayton Wolfe’s writing is slightly obscure, and bad luck is at least somewhat to blame. While many writers drift in and out of the canon, only a few find themselves supplanted by more popular authors with the same name. Indeed, the Tom Wolfe who penned Bonfire of the Vanities (1987) may have, by dint of sheer SEO, made the resurgence of North Carolina native and early 20th century modernist maestro Thomas Wolfe a little slow in coming. But is it finally the original Thomas Wolfe's time?

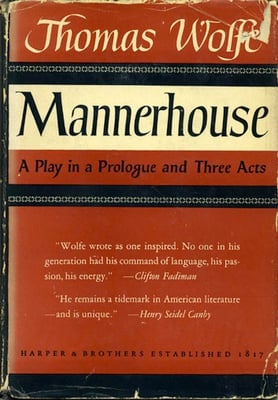

During his lifetime, the original Wolfe, who turned to novels after his plays proved too long to be practically performed, was something of a literary celebrity. His 1929 autobiographical bildungsroman Look Homeward, Angel (1929) gained such acclaim as to earn the young Southerner frequent same-breath mentions with Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and William Faulkner. In fact, Faulkner would be a vocal supporter of Wolfe’s writing, calling him one of the "ablest writers of the generation."

During his lifetime, the original Wolfe, who turned to novels after his plays proved too long to be practically performed, was something of a literary celebrity. His 1929 autobiographical bildungsroman Look Homeward, Angel (1929) gained such acclaim as to earn the young Southerner frequent same-breath mentions with Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and William Faulkner. In fact, Faulkner would be a vocal supporter of Wolfe’s writing, calling him one of the "ablest writers of the generation."

Also among Wolfe’s proponents was Sinclair Lewis, the first American to win the Nobel Prize in literature, who asserted Wolfe’s potential to be “one of the greatest world writers,” during his Nobel lecture.

Despite the almost unprecedented praise the author garnered in his lifetime, his reputation began to falter almost immediately after his untimely death in 1938 at the age of 37. This decline in popularity left his novels (of which there were four, most of them Proustian in length), plays, and short stories to struggle for readers and relevance.

Following Wolfe’s death and subsequent loss of luster, even Faulkner revised his opinion of Wolfe’s work, likening his novels to “an elephant trying to do the hoochie coochie.” The reasons for his falling out of favor are the subject of some debate. Some speculate that the aggressive edits performed on Wolfe’s drafts diminished the effect of the author’s unique style, thereby crippling its chance at longevity. Others wonder if the books simply weren’t that good to begin with.

Whatever the reasons, however, Wolfe’s impact on the twentieth century, though increasingly invisible, proved extremely robust. His distinct blend of epic, autobiography, and modernist style seemed to exist at a uniquely American intersection, comprising the ornate stream of consciousness of William Faulkner with the sustained, close observations of Herman Melville and Nathaniel Hawthorne. As such, his influence can be seen in the works of such writers as Betty Smith, Philip Roth, and Pat Conroy.

Among the most notable of Wolfe’s devotees was Beat writer extraordinaire Jack Kerouac. Though less interested in epic, Proustian tomes, Kerouac borrowed heavily from Wolfe’s signature blend of autobiography and stream-of-consciousness prose to produce some of his best loved works, including On the Road (1957) and The Dharma Bums (1963).

While it was Wolfe’s formal in sights that left a mark on the Beat movement, it was his social insights that influenced the New Journalists. Hunter S. Thompson (a contemporary of the other Tom Wolfe, of Bonfire of the Vanities fame), for instance, actually took the phrase ‘fear and loathing’ from one of Wolfe’s works.

sights that left a mark on the Beat movement, it was his social insights that influenced the New Journalists. Hunter S. Thompson (a contemporary of the other Tom Wolfe, of Bonfire of the Vanities fame), for instance, actually took the phrase ‘fear and loathing’ from one of Wolfe’s works.

Wolfe’s influence is felt most profoundly in the mid-century fiction that, like his own, seeks to mix reality-drawn plots with a sort of formal romanticism, but his impact also extended into the realm of science fiction. Ray Bradbury, in particular, was quite smitten with Wolfe’s work, and it shows. While Bradbury is often thought of as being a high-concept writer, it becomes clear when one thinks about Bradbury in connection to Wolfe that the Farenheit 451 (1953) author’s dedication to craft too often goes unnoticed.

With the reading public seeming to embrace, in recent decades, the sorts of thick volumes that high-school students have historically learned to dread, from David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest (1996) to Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch (2013), it’s possible that the time is finally ripe for Thomas Wolfe to make a comeback in the canon of American literature. When that happens, given the lasting impact that he has had on contemporary letters, it’s conceivable that many will feel like he never left at all.