Are you familiar with the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture? If not, you should be. It’s a division of the New York Public Library (NYPL) system, located on Malcolm X Boulevard in Harlem. The Schomburg Center has a Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division that is open to researchers, in addition to divisions devoted to art and artifacts, moving images, recorded sound, and photographs, among others. There are a lot of good reasons to visit the Schomburg, but today we want to tell you about a recent addition: James Baldwin’s archive.

Resurging Interest in the Writings of James Baldwin

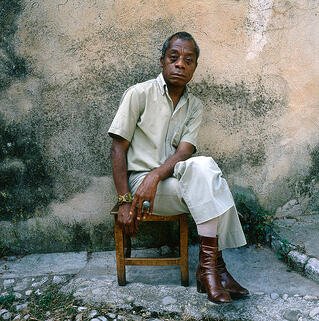

James Baldwin (1924-1987), who the Schomburg describes as a “literary icon and social critic,” was born in Harlem. During his lifetime, he wrote numerous works that addressed pressing issues of racism and inequality in the United States, which remain increasingly relevant today. In recent years, Baldwin’s writings have acquired renewed interest among scholars, filmmakers, and readers alike. For instance, the filmmaker Raoul Peck recently directed I Am Not Your Negro (2016), a documentary that takes as its foundation Baldwin’s unfinished novel Remember This House, which Baldwin imagined as a book about Medgar Evers, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X. Even before Peck’s film, however, readers across the world began flocking—again—to Baldwin’s essays, such as “Letter from a Region in My Mind,” published in The New Yorker in 1962.

James Baldwin (1924-1987), who the Schomburg describes as a “literary icon and social critic,” was born in Harlem. During his lifetime, he wrote numerous works that addressed pressing issues of racism and inequality in the United States, which remain increasingly relevant today. In recent years, Baldwin’s writings have acquired renewed interest among scholars, filmmakers, and readers alike. For instance, the filmmaker Raoul Peck recently directed I Am Not Your Negro (2016), a documentary that takes as its foundation Baldwin’s unfinished novel Remember This House, which Baldwin imagined as a book about Medgar Evers, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X. Even before Peck’s film, however, readers across the world began flocking—again—to Baldwin’s essays, such as “Letter from a Region in My Mind,” published in The New Yorker in 1962.

Needless to say, Baldwin’s language was crucially relevant in the 1960s and throughout his lifetime, and it remains so today. As such, the Schomburg acquisition of the writer’s archive was met with enormous interest.

Schomburg Acquisition of the Baldwin Archive

In April of this year, the Schomburg announced that it had acquired Baldwin’s archive. The Baldwin Papers contains “manuscripts, typescripts, and audio tapes, the breadth and depth of which make it indispensable to understanding fully the significance of Baldwin’s career as a writer and as an engaged public man of letters,” according to the Schomburg Center’s press release. Researchers can access manuscript fragments and edited drafts of Baldwin’s novels, including Go Tell It On the Mountain (1953) and Giovanni’s Room (1956).

In April of this year, the Schomburg announced that it had acquired Baldwin’s archive. The Baldwin Papers contains “manuscripts, typescripts, and audio tapes, the breadth and depth of which make it indispensable to understanding fully the significance of Baldwin’s career as a writer and as an engaged public man of letters,” according to the Schomburg Center’s press release. Researchers can access manuscript fragments and edited drafts of Baldwin’s novels, including Go Tell It On the Mountain (1953) and Giovanni’s Room (1956).

Most exciting—or at least extremely exciting—are the reel-to-reel tapes and audio cassettes in the Baldwin collection. Scholars who don’t specialize in sound or music rarely have the chance to explore this kind of media. The audio materials, as well as the other documents, have been seen (and heard) by very few scholars to date.

In response to the Schomburg’s announcement about its acquisition of the archive, an article in The New York Times noted that, while the bulk of the archive immediately became available to interested researchers, there’s certain correspondence that remains restricted. Letters between Baldwin and figures such as Lorraine Hansberry, Nina Simone, William Styron, and Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis are part of the collection that is open to Schomburg researchers. However, some of Baldwin’s more private correspondence, including that with his brother David and three close friends, will not be accessible.

Given that Baldwin was born and grew up in Harlem, the Schomburg’s acquisition is “a kind of homecoming” for the writer, The New York Times suggests. The acquisition of the Baldwin Papers was made possible by the Ford Foundation, Katharine J. Rayner, James and Morag Anderson, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, and New York Life. To celebrate the new archive, the Schomburg held a short-term exhibition from April 13-22 entitled, The Evidence of Things Seen: Selections from the James Baldwin Papers. Even if you couldn’t make it to the exhibit, visiting the Schomburg at any time of the year would make for an exciting an important research trip.