Rarely does bookbinding receive the attention and glamour afforded other ancient crafts. The craftsmanship required by bookbinding is largely concealed. The role of the bookbinder is that of a guardian; they serve to protect the book's contents to guarantee access for generations of readers. Foremost in the bookbinder's mind is durability and function.

Would we better appreciate and value the complexity of a book's sewing system if we knew why it was sewn in a particular style? We seldom think of the sewing system's purpose since it's hidden from view. Bookbinders, however, do concern themselves with the sewing system utilized in their projects. There are always reasons why these skilled craftsmen and women choose to bind a book in a certain way.

Would we better appreciate and value the complexity of a book's sewing system if we knew why it was sewn in a particular style? We seldom think of the sewing system's purpose since it's hidden from view. Bookbinders, however, do concern themselves with the sewing system utilized in their projects. There are always reasons why these skilled craftsmen and women choose to bind a book in a certain way.

Materials and equipment common to many sewing systems included linen thread of an appropriate thickness, a needle, beeswax to facilitate piercing the binding, unbleached linen tape or hemp cord, paper, pencil and ruler, and a sewing frame and its brass keys. Some of the more common sewing systems were flexible sewing on raised hemp or linen cords; sewing on recessed or sawn-in cords; flexible not to show sewing; and sewing on tapes.

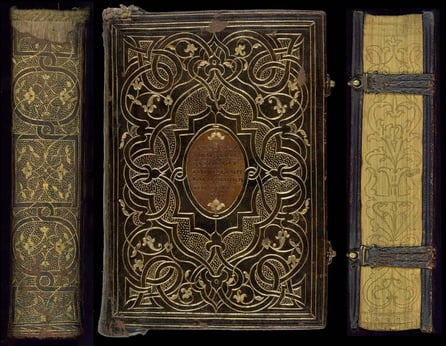

The binding of a book tells you at least as much about a book's provenance as an owner's signature or bookplate, and can often tell you even more. The binding aids librarians and historians when dating a book. It also gives insight into an owner's social and economic standing. Information is imparted about the spread of ideas, technologies, customs, and artistic tastes of a particular time in history. The perceived significance of a book's content is reflected in its binding. The binding tells us how that particular book was intended to be used and how it actually was used.

Evolution of Paper

Papyrus was the first writing material to assume many of the properties of what we know as paper. It was invented by the Egyptians in approximately 3000 B.C. and was made from the leaves of the waterborne papyrus plant. This plant was abundant in the marshy delta of the Nile River. Papyrus was used mostly as a roll or scroll and remained popular until the beginning of the 2nd century A.D.

Parchment as a writing medium predates paper as well. It was thought to have been in use as early as 1500 B.C., though it wasn't credited to anyone until approximately 150 B.C. when Ts’ai Lun of China reported to Emperor Hoti that experiments in making paper from fiber had been perfected.

Parchment was developed in response to the end of Egyptian papyrus exports. Parchment was considered a viable substitute, even though the process of making it was quite messy. It is an animal skin that has been prepared and treated for use in writing, printing or binding.

Vellum is generally made from the entire skin of the animal. Vellum is distinguishable from parchment by its grain and hair marks that create a somewhat irregular surface.

In 105 A.D. it was reported that experiments in papermaking from fiber, like disintegrated cloth, had been successful. The next noteworthy step was documented experiments in making paper from wood pulp fiber that took place from 1765-1772. Wood enabled phenomenal growth in the paper industry and challenged bookbinders to adapt their skills to the new processes.

The bookbinders had to understand how the paper they were working with had been made so they could develop an appreciation of its strengths and limitations. By the middle of the 19th century, they were binding papers that had common ingredients of wood pulp fiber, filler, and sizing.

All the pieces of bookbinding

As knowledge of papermaking spread, it was discovered that paper could be folded and even folded several times. This was the first step in the craft of bookbinding.

As knowledge of papermaking spread, it was discovered that paper could be folded and even folded several times. This was the first step in the craft of bookbinding.

To make each book as solid as possible, most books were beaten before they were sewn. This practice continued through the 1820s. Softer, hand-made paper was capable of being compressed to half the initial thickness using a beating-stone or an iron slab to provide a hard surface upon which the paper could be placed and compressed.

The next step in binding was to sew the sections together that had been collated. The goal was to connect the leaves so that they were firm but easily opened once bound. Sewing was also the best way to attach the book to its cover. There are many different types of sewing methods. It is up to the binder to pick the most appropriate sewing method for a book.

There is always a reason for choosing one sewing method over others, although it is not obvious to an untrained eye. The sewing system provides the foundation upon which the successful accomplishment of all the subsequent binding operations rests. A book is not held together only by the thread used to sew it but the spine linings, boards, headbands, and covering all play a part in the final strength of the book's structure.

The endpapers, or endsheets, are the first and last sheets that protect the text at the beginning and at the end of a book. They take on the strain of opening the covers that would otherwise be on the first and last text sections.

Gluing the spine is to hold the sections together so they do not shift when the book is rounded and backed. These processes were not in use until the 1500s and so glue was not used before then. A variety of glues have been used over time.

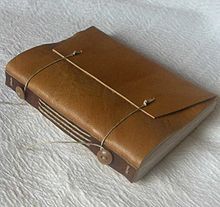

The boards provide the ultimate protection for any book, be it bound or cased. The boards might be wood, paste-board, or something else. Attaching the right boards in the right way is crucial for a book to retain its strength.

Edges of the folded sheets that comprise the sewn textblock need to be cut so every page can be turned. In-board volumes are cut in their boards. The boards are laced on before any edge cutting is done. Out-board volumes are cut before the boards are attached.

Books were so numerous in libraries by the end of the 16th century that a new system was required for their storage. The new method stood the books on end with the spine facing outwards. Binders started using these outward-facing spines to beautify the book, limited only by the binder's imagination.

Publishers began binding their books in cloth around 1830. The cloth binding began as a novelty and a way of advertising as well as differentiating books. This became the norm. Buyers came to see cloth boards as a cheaper alternative to re-binding all their own books.

Leather was an important covering material for books in England since Saxon times. The type of leather is unclear. But volumes of the 12th and 13th centuries appear to have been bound in goatskin.

Dust jackets or dust wrappers are fitted paper coverings that go around the boards of a book. These jackets came into regular use in the latter half of the nineteenth century. They weren't originally intended to be kept with the book, but rather to be used as part of the packaging that would protect the book until it arrived at its final destination. We've written extensively about the history of dust jackets here. The disposal of dust jackets was pretty universal until the early twentieth century. Then, the book's dust jacket became a significant part of a book's desirability.

Bindings That Fail

As you evaluate adding books to your collection that appear to need repair or replacement of bindings, keep in mind the possible causes for bindings to fail. The failure of a binding can be attributed to poor workmanship and inappropriate choice or quality of materials used in the initial binding. The vast majority, however, can simply be chalked up to the passage of time. A good bookbinder will candidly discuss your options and help you make your decision whether or not to repair, replace, or even whether or not to purchase the book with the failing binding.

Sources: University of Adelaide, AbeBooks