The Enlightenment was a period marked with so many innovations in art, science, and philosophy—not to mention all the political power-plays which took place the world over—that it can be difficult to fully unpack all that was accomplished. Book collectors interested in this period are often on the lookout for Daniel Defoe first editions such as the 1719 version of Robinson Crusoe, or the original works of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. James Boswell’s The Life of Samuel Johnson, published in 1791, is another classic of the time. We mustn’t forget, however, that the 18th century gave rise to the field of natural history, and naturalists compiled some of the most interesting and astounding works of the period. One such work is a magnificent bit of art and science, exemplary of 18th century thought and achievement, and worthy of our admiration and study: Johann Jakob Scheuchzer’s magnum opus, Physica Sacra.

Who is Johann Jakob Scheuchzer?

Johann Jakob Scheuchzer was born in Switzerland in 1672. He came of age during the time when the line between science and religion was blurred: one could go to school and complete the same sort of curriculum whether he was hoping to be trained in medicine or theology. For his part, Scheuchzer studied to be a physician. He attended universities in the Netherlands and Germany where he also pursued advanced degrees in mathematics.

Johann Jakob Scheuchzer was born in Switzerland in 1672. He came of age during the time when the line between science and religion was blurred: one could go to school and complete the same sort of curriculum whether he was hoping to be trained in medicine or theology. For his part, Scheuchzer studied to be a physician. He attended universities in the Netherlands and Germany where he also pursued advanced degrees in mathematics.

During his studies and later as an appointed physician and professor, Scheuchzer traveled extensively. He was fascinated with paleontology and natural history. As a result, one of his earliest works was a compilation titled Itinera per Helvetiae alpinas regiones facta annis in which Scheuchzer documented findings on the natural world from his travels. Itinera included detailed descriptions of the formation of the Swiss Alps and the nature and creatures within. Scheuchzer also collected fossils and published his findings in a piece titled Herbarium Diluvianum—which translates to “Herbarium of the Deluge” and references the biblical flood—in the early part of the 18th century.

As did the majority of natural scientists at the time, Scheuchzer used a biblical point of reference for his work. This was a way to frame the overwhelming amount of material being discovered and discussed in the period. Scheuchzer believed that the Old Testament was a factual representation of human history and natural life. He worked to describe the natural law he saw to be governing that which is described in biblical accounts. Among other efforts, he tried to pinpoint when the great flood occurred. Interestingly, he’s often remembered for mis-classifying a skeletal fossil as Homo diluvii testis. He found the fossil in 1725 and believed it to be the remains of a human lost in the flood. His theory was immediately questioned and later debunked in 1811 by Georges Cuvier, and the remains proved to be that of a salamander.

Still, this meshing of the biblical with the natural world was the basis for Johann Jakob Scheuchzer’s masterful Physica Sacra.

What is Physica Sacra?

Physica Sacra is a mammoth publication. It’s a thorough compilation of art, science, and spirituality in which Scheuchzer uses the Bible as his reference point for describing the natural world and its processes. In Physica Sacra, Scheuchzer provides scientific commentary on different bible verses and stories. For example, Scheuchzer argues that the Tower of Babel couldn’t have existed as it was presented and details his reasoning. In short, Physica Sacra is a work of natural theology.

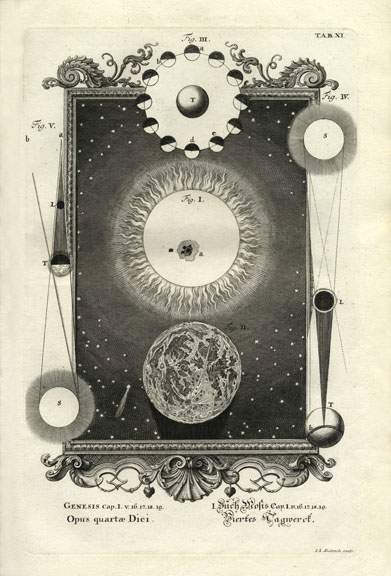

Perhaps the most remarkable aspects of the collection are the images captured within it. Every illustration included references a specific chapter and verse from the books of the 1611 edition of the King James Bible. Physica Sacra is also known as the Kupfer-Bibel which translates to “Copper Bible.” The “copper” in the title is a nod to the prints from the copper plate engravings that make up the masterpiece. There are 762 plates in total, and the images are astounding. The illustrations range in detailing everything from the creation of man and the story of Adam and Eve, to a description of the human heart, to descriptions of snakes, to the creation of the sun and moon, to a detailed list of different kinds of snowflakes, and so much more.

Scheuchzer employed several artists to complete this project, an endeavor that took over 10 years. The sketches were done by Johann Melchior Fussli and a number of engravers worked on the compilation. It’s also well known that Scheuchzer borrowed—or stole—from other artists of the time to add to his work. For example, one of the most famous images in the text, titled “Homo ex Homo” and seen below, includes weeping skeletons first seen in the work of Dutch physician Frederick Ruysch.

Why is it important?

Physica Sacra is a vastly important work for several reasons. First, it is one of a kind. While the practice and study of natural theology occurred before and after the Enlightenment, few works can match the depth and breadth covered in Scheuchzer’s collection. Furthermore, the plates included in this text are astounding works of art. The compilation of over 760 of them is important in and of itself.

The existence of Physica Sacra as a work of natural theology is imperative to our study particularly because of the time in which the author worked. The world was at a crossroads. While religion was still deeply embedded in all aspects of life, scholars were working to reconcile science with a theological belief system. The salamander fossil discussion proves that not long after Physica Sacra was published, scientists and other thought leaders were introducing theories that contradicted tenents of the recent past. As a result, Physica Sacra provides a glimpse into a period of history that was quickly overrun by the continual advancement of scientific ideas. Because it exists, we get to see a manifestation of art and science at a very particular point in the history of human thought.

The existence of Physica Sacra as a work of natural theology is imperative to our study particularly because of the time in which the author worked. The world was at a crossroads. While religion was still deeply embedded in all aspects of life, scholars were working to reconcile science with a theological belief system. The salamander fossil discussion proves that not long after Physica Sacra was published, scientists and other thought leaders were introducing theories that contradicted tenents of the recent past. As a result, Physica Sacra provides a glimpse into a period of history that was quickly overrun by the continual advancement of scientific ideas. Because it exists, we get to see a manifestation of art and science at a very particular point in the history of human thought.

And for his part, by questioning the biblical timeline and some of the stories within and by arguing that fossils were the remains of different creatures, Scheuchzer set the stage for later scholars like Charles Lyell and Charles Darwin. Thus, his work is important both for the time in which it was produced and for the light it shines upon the path to future discovery and scientific advancement.

Sources: Morbid Anatomy, Strange Science, History of Geology, Panteek, Faith in Floods by David R. Montgomery at the University of Washington, Seattle.