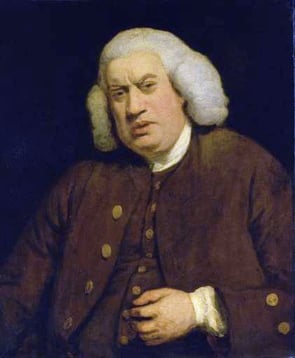

In his infamous 1791 biography of British writer, essayist, and thinker Samuel Johnson, James Boswell wrote: “If nothing but the bright side of characters should be shown, we should sit down in despondency, and think it utterly impossible to imitate them in any thing.”

As it would happen, those words would prove prophetic in the response to Boswell’s The Life of Samuel Johnson, a book often credited with charting the course for what we consider the modern day biography.

Boswell completed and published his biography prior to Johnson’s death after having spent a little less than a year with the British literary icon. The book is praised for its acute attention to detail in painting a portrait of the aging scribe, capturing moments both raw and polished as Johnson discussed his work, life, current state, and possible legacy.

Boswell completed and published his biography prior to Johnson’s death after having spent a little less than a year with the British literary icon. The book is praised for its acute attention to detail in painting a portrait of the aging scribe, capturing moments both raw and polished as Johnson discussed his work, life, current state, and possible legacy.

Boswell labored over creating a version of Johnson that lept off the page with passages like: "a Man of a most dreadfull appearance. He is very slovenly in his dress and speaks with a most uncouth voice."

Having met briefly for the first time only a few years prior in 1763 at Davies Bookshop in London’s Covent Garden, a friendly, albeit loose friendship blossomed after that initial meeting. This budding friendship was largely due to Boswell’s insistence. Thus, the level to which Boswell is able to present his subject is astounding in relation to how little he knew of Johnson’s life prior to their encounter.

But for many, therein lies perhaps the biggest flaw in Boswell’s portrayal: the limited scope and alleged inaccuracies in which Boswell constructs Johnson’s life and personality beyond the 250 days Boswell spent with Johnson.

Critics of Boswell’s biography argue he greatly exaggerated Johnson’s character, personalty, and verbiage, creating a monolith as opposed to chronicling the life of one of the English-speaking world’s most famous writers and thinkers. Some scholars accuse Boswell of editorializing Johnson’s words for greater effect or even inventing entire passages to help fill gaps between anecdotes Johnson related to Boswell during their conversations.

In writing for the New York Times Review of Books*, author Jorge Luis Borges summarizes the creative license Boswell may have taken in his work:

"...Boswell does not reproduce Johnson’s conversation as a stenographer would have done, or a recording, or anything like that, rather that he produces the effect of Johnson’s conversation.”

But proponents of Boswell’s biography — Borges himself even comes to Boswell’s defense in his article — often point to Borges' charge as one of the book’s most effective and influential elements. For literary scholars, Boswell’s ability to capture Johnson’s essence, particularly in the nadir of his life as he slipped further and further from public view, was nothing short of a masterwork.

Borges asserts Johnson was something of peculiar figure — an eccentric, misunderstood man prone to outbursts and fits of social awkwardness who was more or less something of a character long before Boswell’s biographic creation.

While critics of The Life of Dr. Samuel Johnson have remained steadfast in their biting analysis of Boswell’s work, its influence undoubtedly helped shape the landscape of the modern biography, perhaps evidenced most recently in David Lipsky’s intimate portrayal of author David Foster Wallace, Although Of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself: A Road Trip with David Foster Wallace.

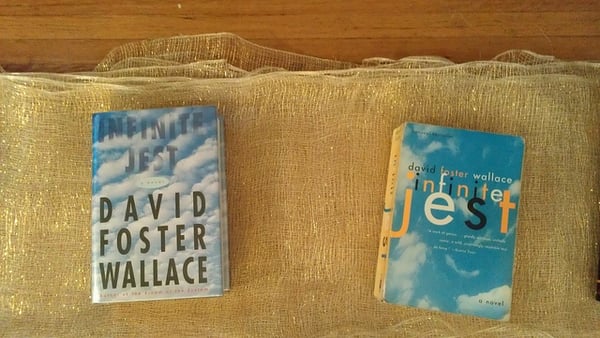

Lipsky’s 2010 book — which is the basis for the newly released film The End of the Tour with Jason Segel and Jesse Eisenberg — documents conversations Lipsky and Wallace had during a five-day road trip at the end of Wallace’s book tour for his breakthrough work, Infinite Jest.

Comprised primarily of transcripts, anecdotes, and sketches while driving from city to city, Lipsky’s book, much like Boswell’s, creates an immediacy in capturing its subject. Both books capitalize on of-the-moment recitations in order to construct as close a likeness as possible to Johnson and Wallace, with both documentarians extrapolating intimate discussions with their subjects in order to create fuller versions of them.

In short, it's not a far stretch to see how Boswell's book influenced Lipsky, who used the tools at his disposal in the time allotted with his subject to reveal, if only in small pieces, a very complicated artist.

Both problematic and masterful, it’s safe to say the echoes of Boswell’s biography are still being heard today, and continue to shape the landscape of the modern biography and its ability to give readers a glimpse into the complexities of the artist’s mind.

*For full text of Borges' New York Times Book Review lecture, click here.