Satire is as old as folly. There have always been abuses of power, mad societies, blundering citizens, and flawed customs. And not far behind them, there has often been a clever observer with a pen. Satirists, as these people are called, use the palliative of humor to address the ills and errors of their time. It’s an impulse that’s as old as time, but just what is it for?

Why Satire?

Satire typically exists to address that which lies in obscurity, either something too unpleasant to confront head-on, or something too ubiquitous to be perceived with the dulled senses. It is the job of the satirist to exaggerate and illuminate these hidden facts and to make them easier to see and deal with. Hopefully, as the laughter subsides, the satirist equips the audience to better redress the maladies he or she has diagnosed.

Satire typically exists to address that which lies in obscurity, either something too unpleasant to confront head-on, or something too ubiquitous to be perceived with the dulled senses. It is the job of the satirist to exaggerate and illuminate these hidden facts and to make them easier to see and deal with. Hopefully, as the laughter subsides, the satirist equips the audience to better redress the maladies he or she has diagnosed.

Yet not everyone takes the joke with high spirits or grace. History shows us that the career of the satirist is full of grave occupational hazards. From Juvenal’s exile from Rome in the first century, to the massacre at the offices of Charlie Hebdo early last year, we see that the comedic and the tragic are not so far apart. Challenging authority, no matter how entertaining, is never without its peril.

Then there’s the other angle, that satire isn’t so effective after all.

In Nazi Germany, it was commonplace for the common people to mock their Führer, his bombast, and his paranoia. They noted how his own “heil” gesture made him look like a waiter carrying a tray. Rudolph Herzog, in his recent book, Dead Funny: Telling Jokes in Hitler’s Germany, examined this reflex for comedy and concluded that it often did little to challenge the regime. If anything, it was a way for the oppressed to blow off steam and from there, continue living placidly under the very powers they detested.

Then again, as Oscar Wilde says: “All art is quite useless.” So perhaps it is best to suspend the demands for practicality and simply enjoy satire for the one thing it certainly is good for: laughter.

A Tried and True Form

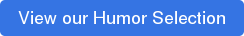

Satirists can work in any form with relative ease, and few genres do so well to welcome playwrights, cartoonists, novelists, TV hosts, and essayists. That same TV personality with an impression of the presidential candidate is part of a tradition that claims the likes of Aristophanes and Horace, Rabelais, and Defoe. As a tried and true form, satire is often one of the first ways a reader understands just how lively centuries-gone writers can be. Aristophanes and Chaucer show us we are far from the first to make below the belt jokes. In the 18th century, famed satirist Jonathan Swift used satire to shine a light on class issues of his day and the changes he hoped to see made. Throughout history, it seems everyone has found mirth and merriment a worthy business, and the topics satirized prove recyclable.

Satirists can work in any form with relative ease, and few genres do so well to welcome playwrights, cartoonists, novelists, TV hosts, and essayists. That same TV personality with an impression of the presidential candidate is part of a tradition that claims the likes of Aristophanes and Horace, Rabelais, and Defoe. As a tried and true form, satire is often one of the first ways a reader understands just how lively centuries-gone writers can be. Aristophanes and Chaucer show us we are far from the first to make below the belt jokes. In the 18th century, famed satirist Jonathan Swift used satire to shine a light on class issues of his day and the changes he hoped to see made. Throughout history, it seems everyone has found mirth and merriment a worthy business, and the topics satirized prove recyclable.

America and Satire

It is natural that a nation as peculiar as America has had many satirists. Our national faults have and continue to attract the finest critical eyes in the world, including everyone from Alexis de Tocqueville to Ta Nehisi Coates.

Benjamin Franklin was a founding father of not only our political tradition, but also our publishing and satirical one. As publisher of periodicals like Poor Richard’s Almanac, he parodied the moods of the nascent country with his epigrams. His vision even reached the most dubious honor of satire, when his own jest anticipated the truth. In recommending to France rising earlier, so as to spend less on candlelight, Franklin inadvertently presaged daylight savings time, to follow nearly a century and a half later.

It is the taste for wit and parody that we see in Franklin that sets the stage for the masterful parodic gazes of Ambrose Bierce and Mark Twain a century later. The United States, if any nation, is one governed by practicality and common sense, where he who goes with his gut typically makes the right choice. Bierce, in his scathing Devil’s Dictionary, satirizes conventional wisdom with definitions like, “FIDELITY, n. A virtue particular to those who are about to be betrayed,” and “PEACE, n. In international affairs, a period of cheating between two periods of fighting.”

It is the taste for wit and parody that we see in Franklin that sets the stage for the masterful parodic gazes of Ambrose Bierce and Mark Twain a century later. The United States, if any nation, is one governed by practicality and common sense, where he who goes with his gut typically makes the right choice. Bierce, in his scathing Devil’s Dictionary, satirizes conventional wisdom with definitions like, “FIDELITY, n. A virtue particular to those who are about to be betrayed,” and “PEACE, n. In international affairs, a period of cheating between two periods of fighting.”

Twain catapulted to success with his his story, The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County, a tale that parodied the tales and myths of frontier life that resonated with the nation. And the nation was happy to have a few jokes slung at the idea of Manifest Destiny politicians so tirelessly talked about. To a contemporary reader, Jumping Frog might not have the same effect, as the Wild West as the butt of the joke has become something of a distant cultural memory. But no American satirist outpaces Mark Twain. He dealt with race, economics, politics, and human nature. He wrote classic sketches long before Saturday Night Live and toured and performed his comedic material long before Richard Pryor. As a comic conscience, there is none like Mark Twain, and we can only hope for successive satirists worthy to be called his heir.

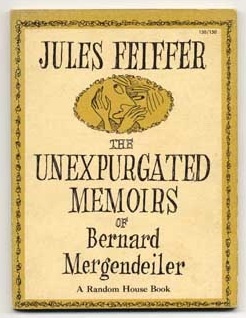

The Great Jules Feiffer

Twain, who was not only a writer but a prankster and speaker as well, embodies the wide range of media that the satirist can exploit. Jules Feiffer exemplifies this. Feiffer began illustrating for comics and magazines in his youth, even working on Will Eisner’s famed The Spirit at the age of seventeen. He ran a longtime column at The Village Voice, which attracted the admiration of Stanley Kubrick (whose Dr. Strangelove shows a great cinematic satirical mind), among others. He has made cartoons for The New York Times and Vanity Fair, and has been called by one critic “the greatest writer now cartooning.” His parodic glance touches upon everything and illuminates the most quotidian things. He gives us dancers who dance on because they love it, although the audience demands a different meaning from it. He gives us wives who shop because they’re neglected. In essence, he gives a frank and clear pronouncement of that which survives by virtue of the opposite—by means of repression, secrecy, and denial.

Twain, who was not only a writer but a prankster and speaker as well, embodies the wide range of media that the satirist can exploit. Jules Feiffer exemplifies this. Feiffer began illustrating for comics and magazines in his youth, even working on Will Eisner’s famed The Spirit at the age of seventeen. He ran a longtime column at The Village Voice, which attracted the admiration of Stanley Kubrick (whose Dr. Strangelove shows a great cinematic satirical mind), among others. He has made cartoons for The New York Times and Vanity Fair, and has been called by one critic “the greatest writer now cartooning.” His parodic glance touches upon everything and illuminates the most quotidian things. He gives us dancers who dance on because they love it, although the audience demands a different meaning from it. He gives us wives who shop because they’re neglected. In essence, he gives a frank and clear pronouncement of that which survives by virtue of the opposite—by means of repression, secrecy, and denial.

And isn’t that what satire is for? The Athenians discovered the faults of their culture in Aristophanes; Italians discovered the follies of the romantic spirit in The Decameron. Are we any different, we who first hear about the latest legislation from an episode of John Oliver’s Last Week Tonight or a headline from The Onion? Or more recently, we who see just a little more clearly the American racial disaster through the fantastical vision of Paul Beatty’s The Sellout? We humans are a peculiar lot, and are inclined to understand better that which is shown to us exaggerated, tampered with, and through the construction of artifice. And isn’t this, in the end, a major virtue of any art?