Russia holds a distinguished place in the vast world of modern literature. Insulated from the larger cultural trends of mainland Europe, it exploded onto the scene in the nineteenth century. It has produced some titanic names—Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Chekhov—and a string of others that will endure through the ages. What caused this impressive boom is unclear, but its origin is far easier to trace. Russia, that powerhouse of modern literature, begins with the poet Alexander Pushkin.

Pushkin was born in the final months of the eighteenth century, on June 6, 1799. Like most writers of his time, he grew up in privileged, aristocratic circumstances. His education consisted of his family’s prodigious library and the company of the many men of letters who visited his home. Pushkin possessed a curiosity and intelligence that displayed itself earlier in his youth. By the time he was a student in an elite private school called the Lyceum, it was apparent that the writer would have a remarkable intellectual life.

Pushkin was born in the final months of the eighteenth century, on June 6, 1799. Like most writers of his time, he grew up in privileged, aristocratic circumstances. His education consisted of his family’s prodigious library and the company of the many men of letters who visited his home. Pushkin possessed a curiosity and intelligence that displayed itself earlier in his youth. By the time he was a student in an elite private school called the Lyceum, it was apparent that the writer would have a remarkable intellectual life.

In 1820, with Pushkin of mere undergraduate age, he published his first major work, the romantic poem Ruslan and Ludmila. Like nearly all of his creations to come, the poem’s strangeness and audacity created a mixed-bag of reception. To some, however, it was clear enough that Pushkin had taken up the unofficial helm as Russia’s poet laureate. V.A. Zhukovsky, the poet’s elder contemporary, noticed not only his influence within Pushkin’s verse but also his obsolescence. He sent a portrait to the precocious talent, with the message: “To the victorious pupil, From the defeated master.”

Pushkin was a radical thinker, and his political (anti-establishment) and religious (atheist) inclinations earned him his fair share of official adversaries. The poet used his position in a clandestine artistic/insurrectionist society to establish the political thought that made for the basis of the doomed Decembrist uprising of 1825. Although not officially involved himself, he was exiled and forced to live in remote parts of Russia, away from cities and areas of influence.

These years of being transferred and shunted around the motherland made Pushkin miserable, but nonetheless proved to be his most fruitful creative period. As the government became more secure in its authority over dissenting radicals, Czar Nicholas I welcomed the popular poet back into mainstream Russian life, and after a long meeting, agreed to be Pushkin’s official censor. Nicholas, however, proved to be more strict than the bureaucratic censors, marking one of the two significant ways Czar Nicholas made the poet’s life more difficult.

These years of being transferred and shunted around the motherland made Pushkin miserable, but nonetheless proved to be his most fruitful creative period. As the government became more secure in its authority over dissenting radicals, Czar Nicholas I welcomed the popular poet back into mainstream Russian life, and after a long meeting, agreed to be Pushkin’s official censor. Nicholas, however, proved to be more strict than the bureaucratic censors, marking one of the two significant ways Czar Nicholas made the poet’s life more difficult.

The other cause of Pushkin’s inconvenience was his position as a low ranking court official, which he was appointed by Nicholas I himself. The reason had less to do with Pushkin’s talents than it did his wife, the (so the record states) astonishingly beautiful Natalya Goncharova. Eminent men throughout Russia, including the Czar himself, deeply admired Natalya. Pushkin suspected that his appointment was, at its heart, a ploy to keep his wife anchored in Russian court society, so she could continue to satisfy the gaze and false hopes of the gentry. Such attention around Natalya’s beauty would ultimately contribute to the author’s ruin.

Eventually, a French military commander took a tenacious liking to Natalya. While many believe that there was never an affair between the two, the Frenchman maintained a cruel and elaborate campaign to torment the Pushkins’ marriage. To the poet’s severe dislike, the Frenchman married Natalya’s sister, with the matter only escalating from there. As an unforgivable act of sabotage, the “other man” sent out a letter to members of Russian court society—including one to Pushkin himself—announcing the poet’s membership to the “Order of the Cuckold.”

Eventually, a French military commander took a tenacious liking to Natalya. While many believe that there was never an affair between the two, the Frenchman maintained a cruel and elaborate campaign to torment the Pushkins’ marriage. To the poet’s severe dislike, the Frenchman married Natalya’s sister, with the matter only escalating from there. As an unforgivable act of sabotage, the “other man” sent out a letter to members of Russian court society—including one to Pushkin himself—announcing the poet’s membership to the “Order of the Cuckold.”

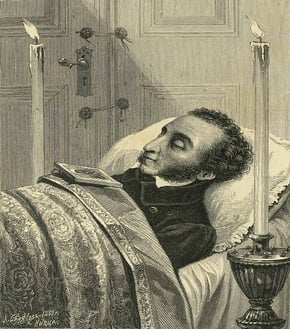

What happened next is famous: Pushkin and his slanderer dueled, resulting in the tragic death of the legendary Russian writer. Aged only 37, Pushkin left behind a body of work and a legacy that only a handful may claim in the whole history of literature.

Unfortunately, Pushkin’s greatness often comes to the detriment of his non-Russian audience. Not unlike Shakespeare, Pushkin revitalized his own tongue, innovating and inventing at every turn. The Encyclopedia Britannica, in a declaration especially bold for an objective biography, credits Alexander Pushkin as “the creator of the Russian literary language.” The magnitude of Pushkin’s achievement means that his work is sheepishly, or at least laboriously, translated into English. In one famous example, the novelist Vladimir Nabokov required two volumes and over seven hundred pages to translate the poet’s hundred-page masterwork, Eugene Onegin. Many more have lamented all that is lost in a translation of the poet’s work. It’s no easy effort to make a titan speak a new tongue, but it’s an essential one if we’re to be reminded that Alexander Pushkin ultimately speaks for us all.