Self-publishing has its detractors, and not without reason. For every success story like Andy Weir’s The Martian (2011) (now a major motion picture starring Matt Damon) or Sergio De La Pava’s PEN Debut Fiction-winning debut, A Naked Singularity (2008) (a sprawling postmodern masterpiece that was picked up by The University of Chicago Press four years after De La Pava’s wife convinced him to self-publish), there are thousands of self-published authors who will languish forever in obscurity. On the other hand, most of the works being published today by major presses will eventually go on to languish forever in their own slightly more prestigious obscurity. Both great and terrible works of literature can (and do) come from anywhere, and there’s no way to know what’s still going to be read a hundred years from now. For proof, here are four famous self-published debuts from literary history.

1. Leaves of Grass (1855)

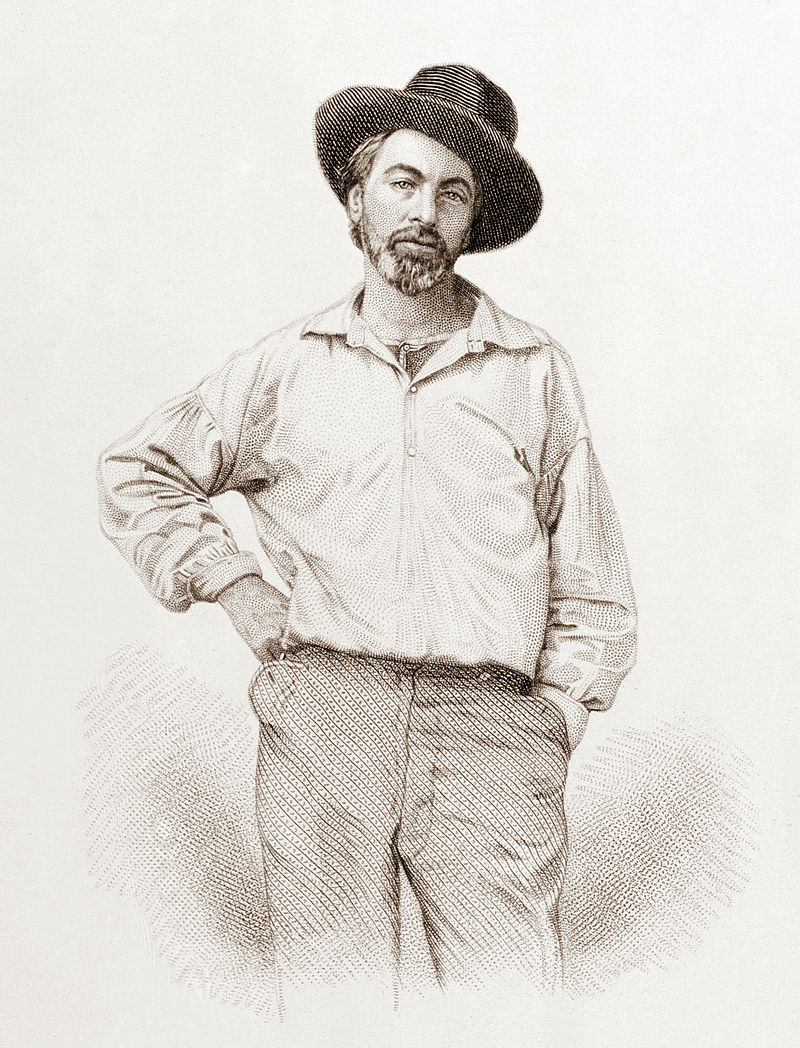

Walt Whitman’s famous collection is perhaps the best example on this list of the idea illustrated above. Inspired by Ralph Waldo Emerson, in the 1840s and ‘50s Whitman wrote the first 95 pages of what would become an overstuffed oeuvre filled to the brim with rugged transcendentalist free verse. Not only did Whitman pay to have the poems published by some friends, he did most of the typesetting himself. Though Whitman’s enduring volume would eventually grow in fame, with Whitman adding new poems in each edition until it contained more than 400, the initial print run of a few hundred did not even bear the author’s name. All that identified the young Whitman as the author was a now iconic image of the poet, arms akimbo in a wide-brimmed hat (see right). Even the name was unassuming, ‘leaves’ being 19th century slang for ‘pages’ and ‘grass’ being a word for inessential works.

Walt Whitman’s famous collection is perhaps the best example on this list of the idea illustrated above. Inspired by Ralph Waldo Emerson, in the 1840s and ‘50s Whitman wrote the first 95 pages of what would become an overstuffed oeuvre filled to the brim with rugged transcendentalist free verse. Not only did Whitman pay to have the poems published by some friends, he did most of the typesetting himself. Though Whitman’s enduring volume would eventually grow in fame, with Whitman adding new poems in each edition until it contained more than 400, the initial print run of a few hundred did not even bear the author’s name. All that identified the young Whitman as the author was a now iconic image of the poet, arms akimbo in a wide-brimmed hat (see right). Even the name was unassuming, ‘leaves’ being 19th century slang for ‘pages’ and ‘grass’ being a word for inessential works.

2. Tamerlane and Other Poems (1827)

Whitman may have left his name off of the initial print run of Leaves of Grass for fear of the cries of obscenity that awaited its publication. Edgar Allan Poe, whose first poetry collection was attributed simply to “a Bostonian,” must have had other reasons. Perhaps he knew, somehow, that the poems would come to be thought of as juvenilia (he claimed to have written most of them before age 14)—or perhaps he was hiding out from his foster father. Either way, Poe paid to have his early verse published by a friend of the family, who printed anywhere between 20 and 200 copies, of which almost none remain. By the time Poe rose to prominence, the book was so hard to find that his own literary executor, Rufus Wilmot Griswold, didn’t believe that it existed. To this day it remains one of the rarest American books.

3. The Tale of Peter Rabbit (1901)

Beatrix Potter's story is often trotted out as an early self-publishing success story, and in some ways it conforms shockingly well to today's such stories. After an initial round of rejections by publishers, who in general did not appreciate the lack of coloration in her illustrations, Potter published 250 copies of The Tale of Peter Rabbit on her own dime. Having done so, she was ultimately able to sell the work to one of the publishers that had initially rejected her—but only after she acquiesced to their demands for color. What's odd about her story is that, having signed a deal with a major children's publisher that would ultimately prove quite lucrative, she kept distributing her self-published volumes, at least to friends and family. In fact, she ordered a second printing of 200 additional copies. One of her self-published editions was even sold to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

Beatrix Potter's story is often trotted out as an early self-publishing success story, and in some ways it conforms shockingly well to today's such stories. After an initial round of rejections by publishers, who in general did not appreciate the lack of coloration in her illustrations, Potter published 250 copies of The Tale of Peter Rabbit on her own dime. Having done so, she was ultimately able to sell the work to one of the publishers that had initially rejected her—but only after she acquiesced to their demands for color. What's odd about her story is that, having signed a deal with a major children's publisher that would ultimately prove quite lucrative, she kept distributing her self-published volumes, at least to friends and family. In fact, she ordered a second printing of 200 additional copies. One of her self-published editions was even sold to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

4. Tristram Shandy (1759)

Laurence Sterne's first novel is widely regarded as one of the first experimental novels written in English. Despite appearing in the 18th century, it anticipates the spirit of modernism and postmodernism with hilarious foresight. It was also self-published (at least for its first two volumes). Sterne went into debt printing the novel, and the fact that he managed to escape that debt with such an odd piece of writing remains slightly miraculous. But what's interesting about Sterne's self-publishing story is not necessarily the publication itself, but its relationship to another self-publishing story that could have been. Sterne's influence was vast, and apparently it extended all the way to young Karl Marx, who composed (most of) a comic novel called "Scorpion and Felix" (I'm laughing already) that was hugely indebted to Tristram Shandy. Marx would never finish or publish the novel in his lifetime, which by all accounts was the correct decision. It remains a deep cut for Marx-scholars hoping to find the strangest possible early inklings of Marx's thoughts on the dialectic.