Many established governments around the globe have a dedicated printing house that handles all official documents and resources. In the United States, it’s the US Government Printing Office. In the British Commonwealth (primarily the United Kingdom and Canada), the role of King’s or Queen’s Printer may be assigned at the monarch’s pleasure. And things get sticky when politics, religion, and publishing mix.

Two historic men stand out for their service as the King’s Printer: Richard Pynson and Robert Waldegrave. Pynson held the title during the reign of King Henry VII and King Henry VIII. The latter monarch, long before his infamous split from the Catholic Church in order to divorce Catherine of Aragon and marry Anne Boleyn, wrote a theological treatise titled “The Defence of the Seven Sacraments.” Henry VIII was a devout Catholic and wanted to speak out against Martin Luther’s attacks on the Church. Richard Pynson was responsible for putting King Henry’s words on paper and sending them out to the world. At the same time, his role as King’s Printer had to be fulfilled along with the demands of his own business. Pynson also published law texts, religious books, classical texts, and even a book that was vaguely science fiction. However, all his other printings were and always will be eclipsed by King Henry's (ironic in hindsight) treatise.

Two historic men stand out for their service as the King’s Printer: Richard Pynson and Robert Waldegrave. Pynson held the title during the reign of King Henry VII and King Henry VIII. The latter monarch, long before his infamous split from the Catholic Church in order to divorce Catherine of Aragon and marry Anne Boleyn, wrote a theological treatise titled “The Defence of the Seven Sacraments.” Henry VIII was a devout Catholic and wanted to speak out against Martin Luther’s attacks on the Church. Richard Pynson was responsible for putting King Henry’s words on paper and sending them out to the world. At the same time, his role as King’s Printer had to be fulfilled along with the demands of his own business. Pynson also published law texts, religious books, classical texts, and even a book that was vaguely science fiction. However, all his other printings were and always will be eclipsed by King Henry's (ironic in hindsight) treatise.

Several generations later, Robert Waldegrave became the King’s Printer to King James VI of Scotland, who later ascended to the English throne as James I. Waldegrave pursued quite a contentious and scandalous printing career prior to his appointment as King’s Printer. He was known for printing works from clergy (mainly Puritans) hostile to the established churches in the late 16th century. Waldegrave was sent to prison for 20 weeks, had his publishing rights restricted, and saw his press and type confiscated by the Stationers’ Company. Without a press and moveable type, a printer was essentially ruined. Waldegrave secretly escaped with a box of type under his clothing and set up a secret press with John Penry, a Protestant preacher. Together, they printed what are known as the Marprelate tracts – short, satirical publications meant to eviscerate the clergy. The tracts were popular but also extremely controversial.

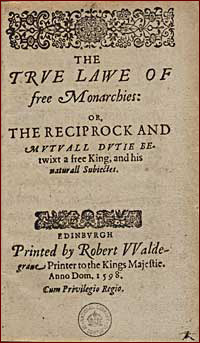

Waldegrave was apparently never connected with the Marpelate tracts, as he was once again granted a license to print in 1590. Months later, he was appointed King’s Printer. James VI of Scotland was a prolific writer, as far as monarchs go. He wrote Daemonologie, The True Law of Free Monarchs, and Basilikon Doron as King of Scotland and “A Counterblaste to Tobacco” as King of England. Unfortunately, Waldegrave died shortly after James’ ascent to the English throne and was not responsible for publishing the last of the King’s writings.

Waldegrave was apparently never connected with the Marpelate tracts, as he was once again granted a license to print in 1590. Months later, he was appointed King’s Printer. James VI of Scotland was a prolific writer, as far as monarchs go. He wrote Daemonologie, The True Law of Free Monarchs, and Basilikon Doron as King of Scotland and “A Counterblaste to Tobacco” as King of England. Unfortunately, Waldegrave died shortly after James’ ascent to the English throne and was not responsible for publishing the last of the King’s writings.

Today, the Queen's Printer, whichever publisher that may be, receives a substantial perk with the title: exclusive printing rights to the King James Bible and the Book of Common Prayer within the United Kingdom. Since the reigning British monarch is also the Head of the Church of England, these two religious publications fall under the attention and care of the king or queen. There are a few exceptions, one of which allows both the Oxford University Press and Cambridge University Press to print the two books regardless of who holds the office of Queen’s Printer.

History is filled with unknown men who brought the writings of kings and queens to the world. In part, we have printers and publishers to thank for preserving our past.