Chris Van Allsburg begins writing his fantasy children’s picture books with a single question “What if…?” and answers it with a string of beautiful and inspiring tales of the extreme. We have some “What ifs…?” of our own. What if a young man with a vague interest in art was denied admission to the University of Michigan because he lacked a portfolio? What if the warmth of that sculptor’s studio kept him away from the inviting apartment with pencils and paper? What if a future Caldecott winner had not married a woman who taught children and hadn’t been encouraged to become a children’s illustrator? What if a Chris Van Allsburg had never come into our collective cultural awareness?

I think we would all agree that our lives and childhoods would have been a little drearier and absent of the magical realism of his incredible works.

I think we would all agree that our lives and childhoods would have been a little drearier and absent of the magical realism of his incredible works.

Chris Van Allsburg did not intend to become an artist of any kind, and even after pursuing this area of study, he did not intend to draw or become an illustrator. Rather he stumbled into the work almost by accident. After wondering out loud in the presence of an admissions officer what A&D stood for and discovering it was “Architecture and Design,” he realized that drawing and art was something that was taught and done professionally and that it might be “fun” to go to college and see what it was all about.

Up until that time he had been without a firm path or direct identity as anything in particular, and he had spent an idyllic childhood chasing minnows in creeks and climbing trees. In 1968, the University of Michigan began requiring a sample portfolio in order to admit students into the art program. However, Van Allsburg ventured into college in 1967 and was a skilled liar who convinced the admissions officer that he had been taking private lessons for years and was proficient in oil paints. Upon being asked what he thought of Norman Rockwell, the boy replied: “‘I believe Norman Rockwell is unfairly criticized for being sentimental. I think he is a wonderful painter who captures America’s longings, America’s dreams and presents American life with the drama and sensitivity of a great playwright.” And with that his fate as an artist was sealed and he began taking classes and developing his voice as a sculptor.

That’s right, the man who would later create such masterpieces as The Garden of Abdul Gasazi began his art career not in drawing but in three dimensional art. He had spent a great deal of his childhood building boats and cars and this seemed like a natural progression of habit, experience, and talent. He not only focused on his sculpting, but excelled at it, graduating and then going into graduate school, and exhibiting in New York City at the Allan Stone Gallery.

The winters in New York are not kind to a sculptor working in his unheated studio and Van Allsburg started staying home and finding comfort doing some sketches with the only materials an artist who does not draw has at hand: pencils and paper. This created the now iconic black and white sketch style so well known to fans of his work. It also started a second, more prolific career for him as an illustrator and writer of children’s books. His wife Lisa noticed his talent, and so did the curator at The Whitney Museum of Art. After he had a show at The Whitney, Lisa’s friend David Macaulay, who was an illustrator and author himself, suggested that the drawings might be good as children’s book illustrations. Chris Van Allsburg chose to write as well as draw, and his first book, The Garden of Abdul Gasazi was published in 1979 and went on to win the Caldecott.

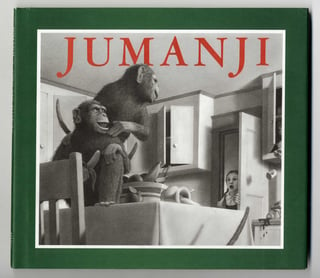

Van Allsburg abandons the normally garish children’s book form and settles—for the most part—on a strictly black and white pallet, requiring more of him with use of patterns, shape, and shadow. The images he creates are haunting in their depiction of a world both familiar and magical. Part of the thrill of reading a Chris Van Allsburg book is that the illustrations appear so commonplace and the story so direct and easily accessible, and then there’s a turn. We see a board game become a fight for survival, and the kitchen—complete with cereal bowls and cupboards—now full of monkeys. A lost dog leads to enhancement, transformation, and a final reveal. A real train in real snow brings a boy the promise of Christmas, and solidifies the magic of the season. It’s the addition of the impossible to the very ordinary that jars the reader into feeling taken out of one reality and placed just off to the left.

Van Allsburg abandons the normally garish children’s book form and settles—for the most part—on a strictly black and white pallet, requiring more of him with use of patterns, shape, and shadow. The images he creates are haunting in their depiction of a world both familiar and magical. Part of the thrill of reading a Chris Van Allsburg book is that the illustrations appear so commonplace and the story so direct and easily accessible, and then there’s a turn. We see a board game become a fight for survival, and the kitchen—complete with cereal bowls and cupboards—now full of monkeys. A lost dog leads to enhancement, transformation, and a final reveal. A real train in real snow brings a boy the promise of Christmas, and solidifies the magic of the season. It’s the addition of the impossible to the very ordinary that jars the reader into feeling taken out of one reality and placed just off to the left.

In these books, the smallest detail or form of an illustration can create a sharp and unsettling tone. The snake in the book Jumanji, for instance, sits on a mantel and the creature almost becomes part of the decorating scheme—echoing the pattern on the living room chair—but remains deadly. The snake is a snake, but the living room is still a living room, and the juxtaposition is what makes it true art.

The storytelling serves the pictures, and vice versa. The end of Jumanji has us observe another pair of children running off with the board game, and the two children having barely escaped with their lives witnessing the incoming of certain danger. This is the mark of a Chris Van Allsburg story; that of the absence of safety and comfort within the context of illustrations both stark and complex.

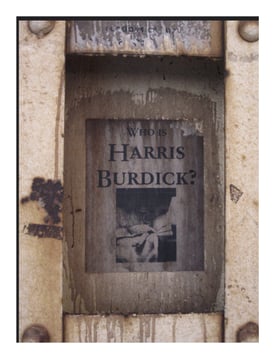

This is the power of a chilling tome entitled The Mysteries of Harris Burdick. This book both frightens and inspires and is metafiction at a complex level rarely seen in children’s literature. The book starts with a story, that of a working illustrator looking for a publisher. To that end, he has prepared a sample of his work, a series of drawings and captions that go with completed stories and books. The publisher reviews this portfolio, expresses great interest, and asks Harris Burdick to come back the next day. The man disappears, never to be seen again. This odd setup brings us to a series of pictures, each encapsulating a moment in a larger story, complete with a strange or almost eerie illustration, and the title of each story introduces and adds another layer to a narrative, never to be written or read. Naturally these “mysteries” have been used as writing exercises in classrooms of all grade levels, and recently an anthology of stories was put out—The Chronicles of Harris Burdick: 14 Amazing Authors Tell the Tales—inspired by the drawings, with writers like Lois Lowry, Stephen King, and Sherman Alexie taking a stab at writing the unwritten.

This is the power of a chilling tome entitled The Mysteries of Harris Burdick. This book both frightens and inspires and is metafiction at a complex level rarely seen in children’s literature. The book starts with a story, that of a working illustrator looking for a publisher. To that end, he has prepared a sample of his work, a series of drawings and captions that go with completed stories and books. The publisher reviews this portfolio, expresses great interest, and asks Harris Burdick to come back the next day. The man disappears, never to be seen again. This odd setup brings us to a series of pictures, each encapsulating a moment in a larger story, complete with a strange or almost eerie illustration, and the title of each story introduces and adds another layer to a narrative, never to be written or read. Naturally these “mysteries” have been used as writing exercises in classrooms of all grade levels, and recently an anthology of stories was put out—The Chronicles of Harris Burdick: 14 Amazing Authors Tell the Tales—inspired by the drawings, with writers like Lois Lowry, Stephen King, and Sherman Alexie taking a stab at writing the unwritten.

Chris Van Allsburg has given us fantasy while making us take a second look at the world around us, and he caught our attention with the muted tones of white, off white, grey, and black. He has restructured the world so we could see it more clearly and all of this began with the question “What is A&D?” And what if it hadn’t been asked? What then?

-About Chris. (n.d.). Retrieved May 11, 2016, here.

-Chris Van Allsburg's Biography. (n.d.). Retrieved May 11, 2016, here.

-Who is Harris Burdick? (2011). Retrieved May 11, 2016, here.-Pierce, T. (n.d.). Chris van Allsburg - Northborough MA [Photograph found in Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository]. Retrieved May 31, 2016, here. (Originally photographed 2011, December 10)

-Casarotto, M. (n.d.). Who is Harris Burdick? [Photograph found in Flickr.com, Chicago, Illinois]. Retrieved May 31, 2016, here. (Originally photographed 2007, July)