To consider the lives lost, the futures thrown into fires, the endless suffering, and the human cost of the atrocity now called “The Holocaust” is more than the human mind could ever process or confront. Instead, we have one representative for those six million. One small voice who illustrates a daily life cut short, who explains the views and the growth of a mind not allowed to see adulthood, one who comes forward to speak for those who are no longer among us. Her name is Anne, and she kept a diary. This is the story of that book.

Most of us who came up through school know the basic story. Anne Frank and her family, along with another family and a dentist, occupied the “secret annex” in a separate part of an office building her father worked in. They went into hiding shortly after Anne’s sister Margot was called to report to a concentration camp. Knowing her fate and that of the rest of the family was bleak, they hid there for two years until, on August 4th, 1944, she and her family were discovered, having been betrayed to the Nazis.

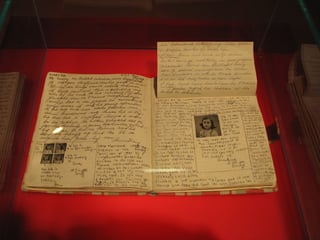

Miep Gies, who had been Otto Frank’s secretary, found Anne Frank's diary after the family had been taken. In hopes that Anne would one day be free, and with respect to her privacy, Miep kept but did not read the diary, and on confirmation of her death, handed the book to Otto Frank. Her diary tells the story of both before the time in the annex and during; we now know that after the diary, Anne died of typhus in Bergen-Belsen.

Of those who lived those two years together, in cramped quarters, with little to look forward to or enjoy, only Otto Frank, Anne’s father, survived the concentration camps. He, like Miep, recognized that this was a private telling, a personal account, and one not initially meant to be shared. In a letter to his mother, Otto Frank delivered the news of the discovered diary in 1945:

"As luck would have it, Miep was able to rescue a photo album and Anne's diary. I didn't have the strength to read it." But later: "I cannot put down Anne's diary. It is so unbelievably engrossing, I will never give up control of the diary because there are too many things in it that nobody should read. But I will make a selection."

Anne had realized that her story, as she was writing it, was an important narrative and one that could explain the circumstances and truth to her experiences and others like it. To that end, Anne had begun to prepare a version that could be published and mentioned her desire to share her story within the diary proper. With this in mind, Otto saw that he was not invading her privacy, but fulfilling her destiny.

Otto edited and transcribed the manuscript, typing up the edited portions into a draft that he then sent to Dutch historian Jan Romein and Annie Romein-Verschoor, who was Jan's wife and also an art historian. They worked to get the manuscript published, but weren’t able to find any takers. On April 3, 1946, Jan Romein wrote a short article about the diary, saying “To me, however, this apparently inconsequential diary by a child... stammered out in a child's voice, embodies all the hideousness of fascism, more so than all the evidence at Nuremberg put together.” She also told about their publishing attempts, and with that small piece, the ball was then rolling and publishers came calling.

It was embraced immediately by a world weary of war and death and looking to grasp for humanity. Anne’s words spoke not of blood or anger or sacrifice, but of humor and romance and the same confusion and angst that we all experience at a young age. The American version of the diary was titled “Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl” which is significant because it defines her identity as that of a young woman, not that of a victim of war. Her diary was just that, the story of a young girl just like any other young girl, and the true impact of the Holocaust was quietly felt in bold letters and in stark imagery.

A great deal is made (and should be) about the editing and censorship of the diary. One of the first real changes, however, was proposed by Anne herself. Anne realized that she might not want to publicly include the real names of the people she discusses, and she made a short list of pseudonyms. Miep Gies, for instance, becomes Miep van Santen, and Peter van Pels is now Peter van Daan. The second voices to ask for changes were those of the editors of Contact, the publishing company finally selected by Otto Frank to publish the diary. Their objections came from a place of conservancy and morality as Anne would often discuss her own body, sexuality, and urges, which they feared might upset or alienate readers.

The years have not changed the attitude about young people and their sexuality, and in 2010, some parents and students in Culpeper County, Virginia worked to have the stark and explicit sexual content in the 50th anniversary “Definitive Edition” (which was published in 1995) banned. Finally it was decided that the old version would be taught and the newer version would be housed in the library. Of the six challenges reported by the American Library Association, "Most of the concerns were about sexually explicit material". In this sense, Anne is done a disservice. Her humanity is spelled out in honest and complete form, from her anger with her mother, to her frustration with her studies, to her yearning to be out of doors. She was also slowly becoming a woman, and her sexuality is part of her story. It is a small tragedy inside of a much larger one that this part of her is set aside, vilified, and ignored as though it is not part of her personal history.

The years have not changed the attitude about young people and their sexuality, and in 2010, some parents and students in Culpeper County, Virginia worked to have the stark and explicit sexual content in the 50th anniversary “Definitive Edition” (which was published in 1995) banned. Finally it was decided that the old version would be taught and the newer version would be housed in the library. Of the six challenges reported by the American Library Association, "Most of the concerns were about sexually explicit material". In this sense, Anne is done a disservice. Her humanity is spelled out in honest and complete form, from her anger with her mother, to her frustration with her studies, to her yearning to be out of doors. She was also slowly becoming a woman, and her sexuality is part of her story. It is a small tragedy inside of a much larger one that this part of her is set aside, vilified, and ignored as though it is not part of her personal history.

Another great insult to the diary is made by those who want to cast aspersions by challenging the authenticity. Those who make these claims are mainly Holocaust deniers who see the book as a fabrication created to lend humanity to an event that never occurred. Eventually the Netherlands Institute for War Documentation put this matter to rest with a series of forensic studies that took scientific tests to the ink, paper, and fabric of the book itself. Six years later, the studies were complete and these tests and handwriting analysis confirmed that the handwriting was that of Anne Frank’s (compared with samples created before the war and before she went into hiding) and that the ink and paper were consistent with those produced in Amsterdam during the time of her youth and internment. Again, these challenges seek to strip away a voice of a writer, clinging to life and experience, as she can feel the fate of her family growing ever closer and ever more desperate. This is a voice that calls out from the dark and asks for empathy, and when challenged, chips away at that small bit of humanity left for us to examine.

Anne died, sick and alone in a camp created to ensure her death. This is her tragedy, and one she shared with millions of others. We read her words of being scolded by teachers, of playing with Peter’s cat to pass the time, of making poetry into presents for holidays and birthdays, of finding humor in the ordinary. For a moment we are there, in the attic, as part of a young girl’s life, but what we are delivered is a life unrealized, a future confirmed but not seen, and a narrative of one of many gone too soon. This is a book that must be shared, in its entirety, often to remind us of what is at stake when too much is taken and so much is precious.

-I Remember Anne Frank. (2005). People, 63(23), 141-144.

-Frank, Anne. (2016). In The Columbia Encyclopedia. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

-Anne Frank Museum Amsterdam - the official Anne Frank House website. (n.d.). Retrieved May 11, 2016, from here.

-Avenant, M. (2016, January 5). Anne Frank's diary published online amid dispute. Retrieved May 11, 2016, here.

-Stitching, Anne Frank. (2007). "Ten questions on the authenticity of the diary of Anne Frank" (PDF).Retrieved May 11, 2016.

-Cowper, H. (2009, April 5). Anne Frank Diary at Anne Frank Museum in Berlin [Photograph]. Flickr.

-Anne Frank (1940) [Photograph found in Collectie Anne Frank Stichting Amsterdam, Amsterdam]. (n.d.). Retrieved May 31, 2016, here. (Originally photographed 1940)