Books encourage people to ask questions. They equip people to understand lives different from their own. They encourage people to seek the truth, to reject what is false and convenient. It is no surprise reading is a powerful thing. For this reason, paranoid governments have always been suspicious of what people might be learning from between the covers of a book. Men might become corrupted. Women might become unchaste. So censors have defamed and condemned them, burned them and banned them—but there will always be people who believe books to be worth fighting for.

While censorship is as old as meaningful writing, the legislation of what can and can’t be read came into full swing in the nineteenth century. As readers became more numerous, and reading material became more accessible, governments became especially interested in what books might be doing to their citizens.

While censorship is as old as meaningful writing, the legislation of what can and can’t be read came into full swing in the nineteenth century. As readers became more numerous, and reading material became more accessible, governments became especially interested in what books might be doing to their citizens.

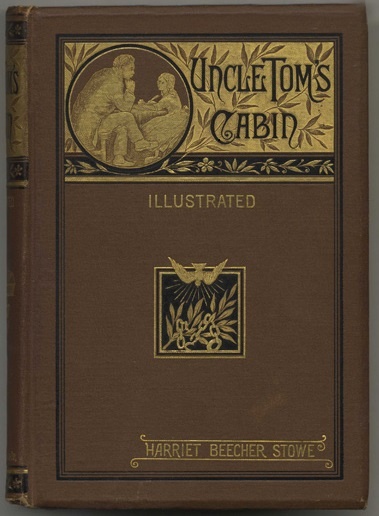

Books Start Wars

There has perhaps been no book in American history as threatening to the status quo as Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which played an essential role in fanning the fires of abolitionism. By dramatizing the horrors of slavery, Harriet Beecher Stowe invigorated a people to oppose their country’s most peculiar institution, and this did not make everyone happy. The Confederacy banned the book for its hostility to their way of life. It outraged Americans, and one person even mailed to Stowe the severed ear of a slave. The book was also banned by Czarist Russia, but it sold more copies in the American nineteenth century than everything but the Bible. It can be hard to overstate the cultural significance of the novel. Abraham Lincoln, upon meeting the author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, is purported to have said “So you're the little woman who wrote the book that made this great war.”

The Golden Age of Censorship

Around a decade after the Civil War’s end, one man came along who would dictate the future of American censorship. His name was Anthony Comstock, a postal inspector whose rigid sense of morality made nearly every piece of photography and writing vulnerable to his censure. He wore big, bushy sideburns, which not only complemented his old-fashioned tastes, but helped conceal a scar left by a pornographer’s knife. With his organization, The New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, and the vast reach of the postal service, Comstock had control over what Americans could read or view for decades.

Comstock and his disciples left behind a literal legacy of ashes. He oversaw the destruction of fifteen tons of books, a few million photos, and countless pieces of printing equipment that was seen as producing a variety of lewd, obscene, and lascivious materials. George Bernard Shaw, whose work was detested by Comstock, called his campaign “the world’s standing joke at the expense of the United States...It confirms the deep-seated conviction of the Old World that America is a provincial place, a second-rate country-town civilization after all." But it was far from a joke to those whose works were vilified, or to the many who were arrested and sued, or to the fifteen people who were driven to suicide by the scandal that rampant “comstockery” left in its wake.

Not even the dead were immune from censorship during this period. Both The Decameron and The Canterbury Tales were banned by the Comstock Laws, despite having failed for five hundred years to uproot the fabric of society. Books by Oscar Wilde, Theodore Dreiser, and pamphlets by doctors writing on contraception were suppressed by the society, too.

A Bold Trio

Three books have come to exemplify the struggle between censorship and art in the early twentieth century. One is D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover, famous for its accusations of pornography, which was banned in the United States since the late 1920s, all the way until its vindication in 1959. You can learn a good deal about the trial and controversy here.

The other two books were Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer and James Joyce’s Ulysses. The former was written by an American author and was published in Paris in 1934. The book had many advocates, including George Orwell. Likewise, Anais Nin, lover and friend of Miller, gave money to the impoverished writer while he composed the book. Among his enemies, Miller had a Pennsylvania Supreme Court Justice, who called the novel “a cesspool, an open sewer, a pit of putrefaction, a slimy gathering of all that is rotten in the debris of human depravity." Tropic of Cancer’s legal controversy in the United States ended in 1964, when the Supreme Court finally declared it not obscene. The classic novel doubtlessly contains vivid depictions of the sexual, as well as about every naughty word you still can’t say on television. The book is decidedly not meant for children, and few would debate otherwise.

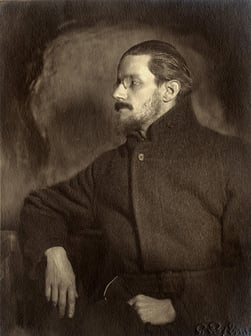

Henry Miller himself was also a fan of the quintessential banned book, Ulysses. Before the influential court case The United States of America v. One Book Called “Ulysses," the novel was contraband in America (a twenty-two year old Ernest Hemingway helped publisher Sylvia Beach smuggle copies in the country). The case crucially marks the moment when censors started to lose their power over serious literature, as it became a popular notion that books that searched for the truth were ultimately more virtuous than vicious. But Joyce’s book was only declared un-obscene in 1933, after an arduous period of fifteen years in which it was decried and defamed by moralists.

Henry Miller himself was also a fan of the quintessential banned book, Ulysses. Before the influential court case The United States of America v. One Book Called “Ulysses," the novel was contraband in America (a twenty-two year old Ernest Hemingway helped publisher Sylvia Beach smuggle copies in the country). The case crucially marks the moment when censors started to lose their power over serious literature, as it became a popular notion that books that searched for the truth were ultimately more virtuous than vicious. But Joyce’s book was only declared un-obscene in 1933, after an arduous period of fifteen years in which it was decried and defamed by moralists.

Case in point, the novel was first published in installments in The Little Review, a small Manhattan-based publication established by Margaret Anderson in 1914. The magazine, which depended dearly on the low shipping rates only the post office could provide, soon found itself crushed by that same institution, empowered by the Comstock laws to inspect and suppress it for the obscenity it contained. Even literary folk echoed the sentiments of the suppressors. Edith Wharton called Joyce's book “a turgid welter of pornography,” and E.M. Forster said it was “a dogged attempt to cover the universe in mud…a simplification of the human character in the interests of Hell.”

The proponents of the now canonical book were also aware of its danger. The enthusiastic Hart Crane declared “some fanatic will kill Joyce sometime soon for the wonderful things said in Ulysses.” Killed he was not, but certainly distressed and discouraged over the clamor of people often too eager to condemn a book they couldn't be helped to read. Now it is a classic, an irrefutable artifact of Western culture, the apotheosis of the twentieth century novel, praised, perhaps, more often than it is read.

While books may still be banned in libraries and schools across the country, it is largely inconceivable that the government would censor printed material as it did up until a half century ago. But banning is perhaps not the worst fate for a book. As Ray Bradbury warned us: “You don't have to burn books to destroy a culture. Just get people to stop reading them.”