The life of W.E.B. Du Bois occupies a remarkable span. He was born in Massachusetts in 1868 to a nation in the middle of its very reconstruction. He took up the mantel of the previous generation of great African-American thinkers, like Sojourner Truth and Frederick Douglass, who themselves escaped bondage. But even with emancipation, America’s work was, and still is, not nearly over. But thanks to the life and work of W.E.B. Du Bois, the United States, and the world, are a little more humane.

W.E.B. Du Bois’ vital 95 years of life trace a path from the ashes of Reconstruction all the way to the blossoming of the Civil Rights movement. He died on August 27th, 1963, the day before Martin Luther King, Jr. proclaimed his dream to the nation on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. Roy Wilkins, a speaker at that event, asked the massive group of marchers to mourn and honor Du Bois with a moment of silence.

W.E.B. Du Bois’ vital 95 years of life trace a path from the ashes of Reconstruction all the way to the blossoming of the Civil Rights movement. He died on August 27th, 1963, the day before Martin Luther King, Jr. proclaimed his dream to the nation on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. Roy Wilkins, a speaker at that event, asked the massive group of marchers to mourn and honor Du Bois with a moment of silence.

Du Bois’ influences are markedly diverse and reflect his catholic intellect. As the first African American to earn a doctorate from Harvard, he studied history and philosophy. His professor, psychologist William James, had a profound impact on him.

While living in Germany, Du Bois even found himself galvanized by German economists like Alfred Wagner. It was this prodigious understanding of many fields— including economics, psychology, and history—that enabled him to contribute to a widespread understanding of culture, politics, and sociology.

Not all of Du Bois’ influences were approached so cozily. In fact, Du Bois was not afraid to challenge his contemporaries. He spoke out against Frederick Douglass’ suggestion that blacks work to integrate with whites. He viewed Booker T. Washington's proposal that education and labor were worth a certain level of obedience to the powers that be as weak, arguing such a proposal was concerned more with order than justice.

The differences between Du Bois and Washington helped to define their era, and prove, as Malcolm X and Martin Luther King did, that activists can fundamentally disagree when approaching the same problem. Washington was much more optimistic about the possibility of a happy relationship between blacks and whites, and courted the support of elites like Theodore Roosevelt and Andrew Carnegie. Du Bois, who sometimes acquired government grants for his reports on black society, was no pariah, but he was not as hopeful when it came to racial harmony.

Du Bois believed in "The Talented Tenth," a term he used to describe black intellectual elites who would work to elevate fellow African-Americans by the promotion of education and financial capability. Through this, he helped found the Niagara Movement, and from that, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which exists to this day.

Du Bois used his pen to address racial problems in their institutional and barbaric forms—often finding that they were not so far apart. There was always the problem of the South, where segregation, voting suppression, lack of education, and simmering violence were ingrained. Du Bois was outspoken against lynching and was inclined to run gruesome photos of murdered victims alongside his writing.

Riots were another frontier for black suffering, and they were often spurred by misplaced anxieties, such as anger at black laborers for undercutting wages and leaving whites unemployed. In the period known as the Red Summer in 1919, some 300 blacks were killed in riots throughout dozens of American cities. In response to such endemic riots, Du Bois organized the Silent Parade, in which nearly 10,000 blacks marched in New York City to protest the nation’s rampant violence. The Parade is considered to be the second such civil rights demonstration in African American history.

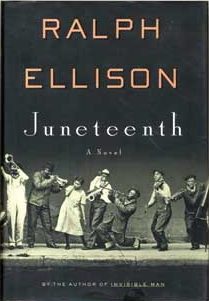

It was often difficult for Du Bois to maintain the distance of a sociologist when examining these outrageous displays of cruelty. Yet his theories, which are so eloquent and well-wrought, galvanized multitudes of later thinkers and artists. Ralph Ellison’s masterful Invisible Man is an heir to the vision and thought of Du Bois, especially in its treatment of black identity and erasure. Du Bois’ writings on “the veil” that conceals and alienates blacks and whites from each other, as well as his famous doctrine of double consciousness, helped give philosophical ground to Ellison's novel.

It was often difficult for Du Bois to maintain the distance of a sociologist when examining these outrageous displays of cruelty. Yet his theories, which are so eloquent and well-wrought, galvanized multitudes of later thinkers and artists. Ralph Ellison’s masterful Invisible Man is an heir to the vision and thought of Du Bois, especially in its treatment of black identity and erasure. Du Bois’ writings on “the veil” that conceals and alienates blacks and whites from each other, as well as his famous doctrine of double consciousness, helped give philosophical ground to Ellison's novel.

Zora Neale Hurston, James Baldwin, and National Book Award winner Ta Nehisi Coates, likewise inherited Du Bois's perspective. He recognized how the grand forces of culture and history have an ever-too-personal effect on black lives on the most intimate of levels.

When one goes beyond his writing, one sees in Du Bois a man who lived through so much, and was able to absorb and reflect upon it with great acuity. He saw the imperialist conflagrations of the World Wars, he saw the repercussions of Reconstruction, he visited the likes of Mao’s China and even Nazi Germany in 1936. He was caught in the crosshairs of McCarthyist paranoia. He oversaw the dignified march for racial progress which would lead to the Civil Rights Act, passed a year after his death. It was a positive culmination for his life’s work, but that does not mean it is done. In looking forward, we can always be helped by looking at the past, and the vital contributions of W.E.B. Du Bois.