In 1853, a Swedish visitor named Per Siljeström noted that “In no country in the world is the taste for reading so diffused among the people as in America.” Alexis de Tocqueville reached a similar conclusion two decades earlier, while surveying the young nation. The French sociologist observed the overwhelming inclination for reading and self-education among the American people. He even went so far as to call this land “the most enlightened community in the world.” The United States began as a nation of bookworms.

A society is often punished for its virtues. All this curiosity and self-education—all these books and letters and pamphlets—had to be controlled. The government established laws. Material was censored and businesses were closed down. People were silenced and sued, arrested and ruined. Some were even driven to suicide. But the national literature was chastened, and the country was doing its job, keeping degenerate thought away from a nation of impressionable adults.

A society is often punished for its virtues. All this curiosity and self-education—all these books and letters and pamphlets—had to be controlled. The government established laws. Material was censored and businesses were closed down. People were silenced and sued, arrested and ruined. Some were even driven to suicide. But the national literature was chastened, and the country was doing its job, keeping degenerate thought away from a nation of impressionable adults.

Dangerous Periodicals

Books are dangerous, but they’re slow. They take a long time to write and spread. The government certainly had its eye on books (more on book banning in America here), but the nation’s censors felt just as threatened by a different literary medium: Magazines. They’re cheap to print. They’re shipped to households nationwide. They give audience to voices and ideas outside the mainstream. People read and discuss them in public: on the train and in cafes. A magazine, to a paranoid and puritanical government, is a most dangerous thing.

The foreigners who bore witness to the book-loving people of antebellum America would be surprised by what happened next. In 1873, President Ulysses Grant signed the Comstock Law, banning any “obscene, lewd, or lascivious book, pamphlet, picture, paper, print, or other publication of an indecent character.” A free and democratic nation was now being told what it could read and write.

Behind the law was the man of its namesake, Anthony Comstock. Now a special agent of the Postal Service, Comstock enjoyed an incredible amount of power and oversight over what America was printing and distributing. From when Abraham Lincoln signed the first postal obscenity law in 1865, about one person per year had been arrested. In his first nine months, Comstock arrested 551.

Behind the law was the man of its namesake, Anthony Comstock. Now a special agent of the Postal Service, Comstock enjoyed an incredible amount of power and oversight over what America was printing and distributing. From when Abraham Lincoln signed the first postal obscenity law in 1865, about one person per year had been arrested. In his first nine months, Comstock arrested 551.

Comstock set a strong standard for moral censorship. He ended his career having helped to convict 3,000 peddlers of indecent material. In total, about 50 tons of books were destroyed during his tenure. And 16 people who were ruined by these censorship laws took their own lives.

Getting Political

Things only got worse for publishers, printers, and writers with the coming of the First World War. Censorship was no longer about merely protecting the moral sensibility of the nation, it was a matter of national security. With the passage of the Espionage Act in 1917, the government was given more power than ever to suppress written material. Anyone who was seen to advocate against the war effort could be seriously punished.

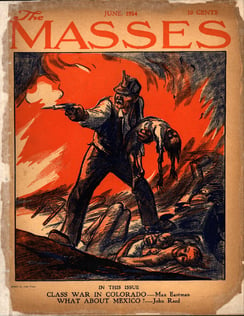

One didn’t have to do much to be considered insubordinate. Isolationist, anti-enlistment, and pacifist arguments were frequently censored. As were radical thinkers, especially communists and anarchists, who were reflexively lumped in with the enemy. A magazine called The Masses was convicted of obstructing military enlistment. Max Eastman and the magazine’s associates were threatened with $10,000 in fines and up to 25 years in prison. Some months prior, Emma Goldman’s Mother Earth was also victim to the post office’s watchful eye. Goldman, an unapologetic feminist and anarchist, was never a darling of the United States establishment. Government agents gleefully shut the magazine down in 1917, and raided its files to track down its friends and allies. This raid led the government to one more pesky periodical, which went by the name of The Little Review. It was within this small magazine’s pages that censors found passages from a book called Ulysses. The fight for the century’s major novel began in the pages of a magazine, and would change the face of American censorship forever.

One didn’t have to do much to be considered insubordinate. Isolationist, anti-enlistment, and pacifist arguments were frequently censored. As were radical thinkers, especially communists and anarchists, who were reflexively lumped in with the enemy. A magazine called The Masses was convicted of obstructing military enlistment. Max Eastman and the magazine’s associates were threatened with $10,000 in fines and up to 25 years in prison. Some months prior, Emma Goldman’s Mother Earth was also victim to the post office’s watchful eye. Goldman, an unapologetic feminist and anarchist, was never a darling of the United States establishment. Government agents gleefully shut the magazine down in 1917, and raided its files to track down its friends and allies. This raid led the government to one more pesky periodical, which went by the name of The Little Review. It was within this small magazine’s pages that censors found passages from a book called Ulysses. The fight for the century’s major novel began in the pages of a magazine, and would change the face of American censorship forever.

Modern Cases

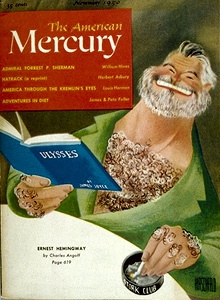

The Comstock Law and its legacy would take a long time to die off. H.L. Mencken founded The American Mercury, a prolific literary magazine that published the likes of W.E.B. Du Bois, William Faulkner, Sinclair Lewis, and F. Scott Fitzgerald. In 1926, The American Mercury featured a story about a repentant prostitute. Called “Hatrack,” the story was challenged by the Watch and Ward Society, the Boston equivalent of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice founded by Comstock in the century earlier. Mencken was first challenged by an official of the society, and later by a government prosecutor citing the Comstock Law. Mencken cheerfully stirred up publicity and photo opportunities along the way, and felt confident in his protection under the freedoms of press and speech. Mencken did win in the eye of the law, but not without a great financial cost to himself and his magazine.

This puritanical censorship is rather foreign to us today. At least, the focus on moral purity has shifted to more-consumed media like film and television. Political censorship, akin to what we saw in World War I, is the mode of contemporary times. In 1971, The New York Times obtained documents exposing the misdeeds of the federal government, called the Pentagon Papers. Editor Daniel Ellsberg was charged with espionage and theft of government property, but was acquitted when a federal smear campaign was uncovered. Today, newspapers are threatened not as much by penalty but by a secretive government. Many of today’s important stories, whether popular or not, come from leaks of protected information. Edward Snowden and NSA, as well as reports on the realities of drone warfare, come to us by way of people on the inside who risk prosecution to disseminate the truth.

The truth, like good writing and attentive readers, is a dangerous thing. Whether in the form of aesthetic vision or journalistic research, it has the power to change hearts and minds. We should make sure to live in a culture that embraces such danger, even when laws and institutions would have us do otherwise.

1. Birmingham, Kevin. (2014). The Most Dangerous Book: The Battle for James Joyce's Ulysses. N.p.: Penguin.