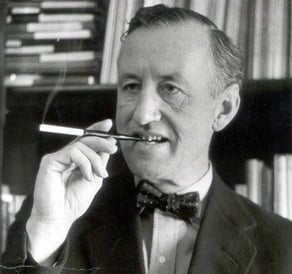

If there’s one overarching fear authors experience when creating novel series, it’s repetition—drudging up the same plot twists and themes and motifs novel after novel until each story essentially becomes a parody of itself. In fact, Ian Fleming expressed that very sentiment to friends and confidants during the early stages of writing his third Bond novel, Moonraker.

But if Fleming had any anxieties about rehashing material from Casino Royale and Live and Let Die, those trepidations did not present in the final product. Moonraker, which many consider to be Fleming’s best Bond novel—noted author and close friend Noel Coward remarked as such to Fleming and in the press on several occasions—strives for greater depth and complexity than Fleming’s previous Bond novels, investigating both the quieter aspects of Bond’s personal life and the state of British culture and identity in the early 1950s, post World War II.

Yes, all the trappings of classic Bond are in Moonraker—intrigue, adventure, romance, glamour, and style. But these elements work to serve a greater purpose than to merely thrill or excite. Fleming’s examination of the proliferation of nuclear weapons, political paranoia, and themes of ‘the traitor within’ explore new territory while simultaneously paying homage to the character readers came to adore.

Yes, all the trappings of classic Bond are in Moonraker—intrigue, adventure, romance, glamour, and style. But these elements work to serve a greater purpose than to merely thrill or excite. Fleming’s examination of the proliferation of nuclear weapons, political paranoia, and themes of ‘the traitor within’ explore new territory while simultaneously paying homage to the character readers came to adore.

It’s as if Fleming’s insecurities about repeating himself forced him to pull out all the stops on Bond’s third go-around, and the results were another high-flying, compelling story of the world’s most beloved spy.

The Mission

Moonraker opens with an intimate, revealing portrait of Bond’s personal life in London. Bond is essentially living a somewhat routine day-to-day existence, and the reader is privy to his love of the gentleman’s clubs of the day—card playing and enjoying finely made beverages in the late afternoon and evenings—a real bon vivant lifestyle. However, M quickly assigns Bond to observe a shady character at one of these clubs named Sir Hugo Drax, who M suspects is cheating fellow card players out of money.

Drax is perhaps the most mysterious Bond villain to this point. Presumed to be a British solider who was badly wounded during a World War II battle, Drax was discharged from service and returned to London where he made a substantial living as an industrialist and member of high society. Since his return to civilian life, Drax’s industrial empire has been commissioned to build Moonraker, Britain’s first nuclear missile program for defense against Communist and other intruding forces.

After a Ministry of Supply officer is killed while working at the Moonraker production facility, M directs Bond to infiltrate the facility undercover and ascertain exactly the status of Moonraker and Drax’s involvement in the project. Bond meets Gala Brand, another undercover British spy posing as Drax’s assistant, who also believes Drax’s intentions with Moonraker may be less than pure.

It’s not long before Brand and Bond are both found out as undercover spies, and Drax kidnaps Brand to a secret location in London where she learns the intended target for the initial Moonraker launch is London. Bond gives chase after Brand but is ultimately captured, which is when the story behind Drax’s true identity begins to unravel.

While detaining Bond, Drax reveals he is actually a former German commander dead-set on revenge against Britain for World War II. He tells Bond he plans to aim Moonraker at central London, but also plans to play the stock market in the days prior to amass a great fortune. In the end, Bond escapes, and with Brand’s help, they redirect the Moonraker launch to splash down in the sea, killing Drax in the crossfire as he attempts to escape in a Russian submarine.

FAQ

Fleming originally conceived Moonraker as a screenplay several years before he began writing the novel—in fact, Fleming may have actually had a sizable chunk of the screenplay complete when he arrived at his Goldeneye estate in Jamaica in 1954 to begin work on the novel. Though the end result varied wildly from Fleming’s early work, his writing process remained unchanged—a few hours in the morning, a few in the evening, with very little editing along the way.

In an effort to distinguish Moonraker from the previous two Bond novels, Fleming decided to set the novel entirely in Britain, eschewing some of the more exotic locations usually associated with Bond. Rather than fall back on Bond’s globe-trotting as a character and narrative device, Fleming wanted to display a more nuanced part of Bond’s personality—at least in the novel’s early portions—as well as Fleming’s love for his home country. In fact, many Bond scholars have called Moonraker Fleming’s hymn to England, and especially to London.

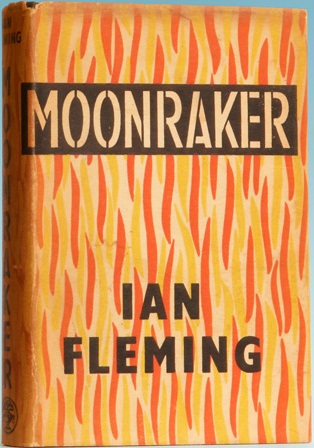

Moonraker was released by Jonathan Cape in Britain on April 5, 1955 to brisk sales and rave critical reviews. A paperback edition was released roughly a year later, and an American edition was published in December 1956 under the title Too Hot to Handle with a heavy editorial bent on clarifying and adapting British idioms for American readers.

Field Notes

Several factors contribute to Moonraker being one of the more ubiquitous Bond volumes on the market. First, due to the success of the first two Bond novels, more hardcover, first editions were published—just shy of 10,000 for the British first edition, with a paperback run of 43,000 copies. Secondly, the publication of the aforementioned American version under a different title also helped flood the marketplace. And lastly, because the 1979 film adaptation varied widely from the novel, a second novelization was published titled James Bond and Moonraker, which stuck closely to the film’s plot and was panned almost universally by critics and audiences.

Several factors contribute to Moonraker being one of the more ubiquitous Bond volumes on the market. First, due to the success of the first two Bond novels, more hardcover, first editions were published—just shy of 10,000 for the British first edition, with a paperback run of 43,000 copies. Secondly, the publication of the aforementioned American version under a different title also helped flood the marketplace. And lastly, because the 1979 film adaptation varied widely from the novel, a second novelization was published titled James Bond and Moonraker, which stuck closely to the film’s plot and was panned almost universally by critics and audiences.

British first editions of Moonraker feature vibrant orange and hash marks reminiscent of fire or an explosion with silver font for the front cover and spine. The cover was designed in a partnership with Fleming and Kenneth Lewis, who created the cover design for the second Bond novel, Live and Let Die. As with all first editions, the name of Fleming’s publisher, Jonathan Cape, should appear prominently on the inside title page, which should also not contain any additional credits or references to those who helped bring the novel into production.

The Bond Dossier will return with Diamonds Are Forever...

For past features, see The Bond Dossier: Casino Royale and The Bond Dossier: Live and Let Die.