If you like reading books, it’s probably to be taken into new narrative worlds: to explore vast, dramatic landscapes of knowledge and discovery. What you might be less interested in, however, is the legal architecture that makes that very book possible. Intellectual property laws make up a necessary system that protects the author’s creation and the publisher’s investment. It lies at the intersection between art, business, and government, and purports that it is a society’s duty to regard the preservation and health of its culture.

Given the inefficiency of copying by hand, there was minimal need for copyright protection for centuries. There were only so many copies owned, and only so many literate readers to distribute them to. Besides, if you were being copied—whether in Alexandria’s libraries, the universities of Muslim Spain, or the monasteries of Ireland—odds were very high that you were dead anyway.

Given the inefficiency of copying by hand, there was minimal need for copyright protection for centuries. There were only so many copies owned, and only so many literate readers to distribute them to. Besides, if you were being copied—whether in Alexandria’s libraries, the universities of Muslim Spain, or the monasteries of Ireland—odds were very high that you were dead anyway.

Copyrights found currency with the advent of the printing press and the growth of a literate public. In England, intellectual property rights were established as early as 1662. Even earlier was the precedent of the King’s printer, who had exclusive rights over the King James Bible and other texts. Britain passed a copyright law in 1709, often called the Statute of Anne, which proved to be seminal legislation in granting the power to government to enforce protections and punish infringements of copyright.

The United States, being a proprietary nation, announced its preference for innovation and creativity immediately. In fact, it’s incorporated into the nation’s legislative DNA. According to the Constitution, Congress is authorized

to promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.

In the United States, these rights typically last seventy years after the author’s death, before entering the public domain.

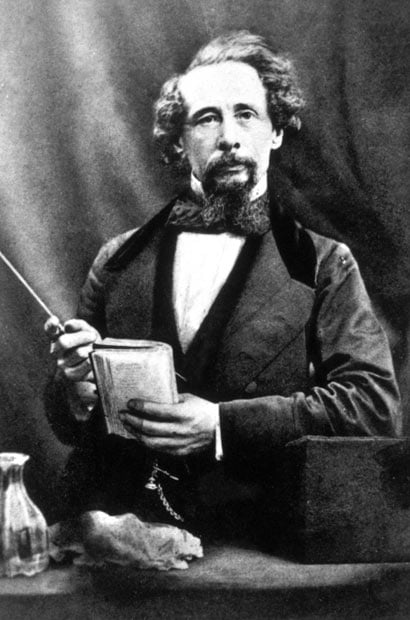

These early national laws had their shortcomings, of course. In the nineteenth century, Charles Dickens became famous for condemning the pirated copies of his novels in America. Of course, he received no money from them, nor did his American contemporaries (like Washington Irving and Walt Whitman) whose works were printed without authorization in Britain. In the late nineteenth century, namely with the Berne Convention of 1886, copyright laws began being internationalized, making it harder for renegade printers to turn a profit.

These early national laws had their shortcomings, of course. In the nineteenth century, Charles Dickens became famous for condemning the pirated copies of his novels in America. Of course, he received no money from them, nor did his American contemporaries (like Washington Irving and Walt Whitman) whose works were printed without authorization in Britain. In the late nineteenth century, namely with the Berne Convention of 1886, copyright laws began being internationalized, making it harder for renegade printers to turn a profit.

Yet copyright, like any legal principle, is constantly being reconceived in response to changing times and circumstances. Below are some notable copyright cases in the United States.

Folsom v. Marsh (1841)

Copyright laws frequently depend on weighty metaphysical arguments, necessary to distinguish what makes something original, appropriative, diminishing, or derivative. One of the earliest cases, settled in 1841, concerned an abridgment of a twelve-volume edition of George Washington’s biography. Issues raised in the trial included (i) whether abridgment was infringement, (ii) whether the concise edition would injure the original work’s sales, and (iii) whether the original biography organized the letters of Washington (which would otherwise be public domain) in a proprietary, and therefore copyrightable, way. The court ruled in favor of the original work, and further established the rights of the creator to decide how her work is used by separate parties.

Baker v. Selden (1879)

At the center of this case is the idea-expression divide. A man named Charles Selden wrote a book about library organization, and wished to extend control over the practice of his methods. While the court ruled that Selden retained copyright over his work, he could not profit from or suppress people who followed those examples he outlined. This case made clear that copyright cannot protect ideas themselves, only their expression.

Harold Courlander v. Alex Haley (1978)

Harold Courlander wrote the novel The African several years before another book, Roots, came out bearing some remarkable resemblance. With a smash-television series and massive sales, what followed the success of Roots was one of the most notable plagiarism cases in recent memory. In the court memorandum, Courlander’s argument stated

Harold Courlander wrote the novel The African several years before another book, Roots, came out bearing some remarkable resemblance. With a smash-television series and massive sales, what followed the success of Roots was one of the most notable plagiarism cases in recent memory. In the court memorandum, Courlander’s argument stated

Defendant Haley had access to and substantially copied from The African. Without The African, Roots would have been a very different and less successful novel, and indeed it is doubtful that Mr. Haley could have written Roots without The African.... Mr. Haley copied language, thoughts, attitudes, incidents, situations, plot and character.

Few could deny the similarities, and it became clear enough that Roots’ literary integrity depended significantly on the contents of The African. The lawsuit was settled out of court for $650,000, with Haley issuing a statement that he did rely on the plaintiff’s book to write his own novel.

Community for Creative Non-Violence v. Reid (1989)

This Supreme Court case established that while it is the general rule that the author of a work retains copyright, this condition may be changed by contract. Of course, intellectual property can be owned not by individuals but by businesses and institutions, meaning big bucks for those entities in charge. Licensing is a major leg of the media industry, and many properties, like Star Wars, Harry Potter, and Winnie-the-Pooh gross billions of dollars annually.

The consequences run even deeper. Where people and estates die, the lifespan of a corporation is not definite, meaning material can be locked into copyright for far longer periods than usual. The songs of Irving Berlin, for instance, belong to a monopoly that will retain rights to them for 140 years. At the heart of a case like this is the question of whether certain copyright protections work to hoard and hinder creativity.

Copyright laws were made to strengthen and encourage cultural contributions, and we should be diligent to challenge them if they fail to meet those ends. In changing times, it is important to remember our intentions.