At last, it is time to read your new book. It is a crisp evening and you have made a cup of your favorite tea. You splurged and even made a fire. You sink into your chair and look at the book’s cover, tracing the title with your fingertip. You sip your tea and open to the first page. Blank. You turn the page. Nearly blank, except for the title—again. With some impatience, you turn to the next page. Here the title is presented a third time but with the welcome addition of the author and publisher. Your tea nearly finished, you quickly flip past the table of contents, list of illustrations, author’s note, preface, introduction, and dedication. As your fire burns out, you reach page one.

|

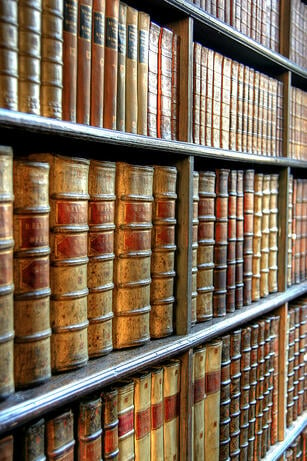

| In signed first editions, the author's signature can often be found on the half-title page, as is this signed copy of Paolo Coehlo's The Alchemist. |

As any reader knows, a book can offer a vast amount of information before the “first” page. But why, one wonders, do some books display the title no less than three times in succession? None will dispute the cover: printing the title there seems obvious and right. Even the title page, listing the title, author, and publisher, passes with little argument. But why this in-between page, this unneeded repetition between the two? Why, in the words of old-fashioned bookbinders, this bastard title?

The Origins of the Bastard Title

The bastard title, also known as the half-title, has its origins in the very beginnings of printing. Prior to the mid-nineteenth century, book printing and bookbinding were two distinct trades. Printers would produce the pages of a book and sell these text-blocks to the public. Individuals would have their personal bookbinder cover the pages to match the rest of their library. For this reason, a text-block—the unbound book—would circulate quite a bit before being enclosed in leather or wood.

To protect the title page, publishers in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries printed books with a blank page on top. Printers would produce less than a hundred books at a time for patrons who had paid in advance. Distributing unmarked text-blocks in such quantities was little inconvenience. By the seventeenth century, however, books were produced in larger quantities and many were sold to professional booksellers. Bookshops of this era bore no resemblance to those we know today. Text-blocks remained unbound and were stacked in bins that covered the walls of the store. Sellers organized their inventory by labeling the bins, but there were frequently stacks of assorted, unlabeled books. To help these booksellers, printers began printing the title on the outside page. Soon it became standard practice, and the bastard title was born.

The Bastard Title and Book Storage

In this era, bound books were not stored upright on shelves with their spines facing outward. Rather, books were stacked with their spines facing in. Individuals often handwrote the book’s title on the fore-edge of the book. Once the bastard title became common, book owners began using them to organize their libraries. Instead of handwriting the title on the fore-edge, they cut out the bastard title and pasted it inside the cover, folding it over the fore-edge and thus labelling the book. By the mid-eighteenth century, people began reorganizing their libraries with the spines facing out; they would cut out the bastard title and paste it on the spine of their books.

Finally, in the nineteenth century, bookbinders printed the title directly on the spine. The bastard title consequently served no purpose after a book was bound. This gave rise to considerable controversy—should a bookbinder include the bastard title or remove it from the bound book? Some considered the bastard title entirely dispensable, while others believed it to be an integral part of the book. Most book owners preferred to retain the bastard title and were annoyed if their bookbinder removed it against their wishes.

To Be or Not to Be?

In the mid-nineteenth century, publishers began binding as well as printing books. They generally included the bastard title as it was then common practice to do so. Yet towards the end of the twentieth century, the bastard title went into decline as publishers tried to reduce costs. Initially it was only removed from paperback and softcover books, but today it is frequently absent in even hardcover books. Is this piece of publishing history doomed for extinction? Inspect your own library and favorite bookstore, then decide for yourself.

Have a question about a book-related term? Check out our glossary below!

A Glossary of Book Terms Part I: The Anatomy of a Book

If you're just getting into antiquarian or rare book collecting, you may be overwhelmed by the terms and phrases bandied about in item descriptions. What's a frontispiece? What is foxing in books? What's the difference between a galley and an advance reader copy? We hope to shed some light on the jargon of the book trade in a series of glossary posts, starting with the anatomy of a book.

Boards – The stiff material commonly referred to as the covers. Historically made of wood, but most modern binders use cardboard.

Boards – The stiff material commonly referred to as the covers. Historically made of wood, but most modern binders use cardboard.

Colophon - A statement, often placed at the end of a book or manuscript, with facts relative to its production. It typically includes the name of the printer, type of paper and typeface used, and may state the number of books printed in this edition. The term is also used to describe an identifying mark, emblem, or device used by a printer or a publisher.

Cuts - Woodcut illustrations often printed on the same pages as the body of text.

Dust-Jacket - The paper jacket which is wrapped around most modern books to protect the cloth covers. Sometimes called a dust-wrapper, it often includes information about the book and author. The earliest recorded dust-jackets date from the early nineteenth century.

Endpapers - Endpapers are the double leaves added at the front and back of the book by the binder. The outer leaf of each is pasted to the inner surface of the cover board (referred to as the pastedown), and the inner leaves (or free endpapers) form the first and last pages of the volume when bound or cased. Endpapers can be plain or highly decorated, as with marbling. The pastedown is often where a bookplate is found.

Fly-Leaf - A binder's blank following, the front free endpaper or preceding the rear. Often used for the front free endpaper itself.