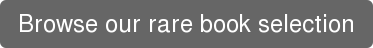

For most of the Middle Ages, the only way to reproduce a book was to copy it by hand. Copying was solitary, lengthy, and physically taxing work. Scribes worked long hours, in contorted positions, and abided by rigid expectations. At heart, it was a droning process, too, allowing the copier only the ability to transfer the words of another. Consequently, many scribes developed a sense of humor to break up the monotony of their hand-cramping task. It was well-deserved, for without these scribes, we would have lost an unfathomable amount of our artistic and cultural history — from antiquity onward. Luckily, we can find evidence of their playful spirits in the margins of their very manuscripts, where illustrated miniatures and writings reveal the creative personality behind the pen.

Complaints

Copying a book by hand had a good deal of inconveniences. It involved working on a slanted platform, designed to aid visibility and the flow of ink. While this arrangement was good for the tools, it took a toll on the the scribe’s body. It also meant straining one’s eyes. The entire ordeal brought boredom and solitude. It is no surprise that the scribes often used the margins to complain. The following querulous confessions have all been found in the pages medieval manuscripts:

Copying a book by hand had a good deal of inconveniences. It involved working on a slanted platform, designed to aid visibility and the flow of ink. While this arrangement was good for the tools, it took a toll on the the scribe’s body. It also meant straining one’s eyes. The entire ordeal brought boredom and solitude. It is no surprise that the scribes often used the margins to complain. The following querulous confessions have all been found in the pages medieval manuscripts:

“Thank God, it will soon be dark.”

“Writing is excessive drudgery. It crooks your back, it dims your sight, it twists your stomach and your sides.”

“Oh, my hand.”

“As the harbor is welcome to the sailor, so is the last line to the scribe.”

“It is very cold.”

“St Patrick of Armagh, deliver me from writing.”

“The work is written master, give me a drink. Let the right hand of the scribe be free from the oppressiveness of pain.”

One Henry of Damme, who wrote a chronicle of Brussels, complained about his poor compensation:

“11 golden letters, 8 shilling each; 700 (initial) letters with double shafts, 7 shilling for each hundred; and 35 quires of text, each 16 leaves, at 3 shilling each.” He wrote in Dutch. Then, in Latin: Pro tali precio nunquam plus scriber volo: “For such an amount I won’t write again!”

While other complaints are of sheer cosmic despair:

“This is sad! O little book! A day will come in truth when someone over your page will say, ‘The hand that wrote it is no more.’”

The Equipment

Transcribing was labor intensive, and we can understand the frustration of a scribe whose rigorous effort was squandered on inferior materials. These complaints voice these anxieties, quite clearly:

“The ink is thin.”

"Let me now be blamed for the script, for the ink is bad, and the vellum defective, and the day is dark"

"A curse on thee, O pen!"

"Cithruadh Magfindgaill wrote the above without pumice, and with bad implements"

“This parchment is hairy.”

Parchment was made from animal skin, typically that of a cow, sheep, or goat. The best parchment came from unborn animals, and was very expensive. It was not uncommon for lower grade parchment, which was more cost-effective, to contain holes and un-writable portions.

Parchment was made from animal skin, typically that of a cow, sheep, or goat. The best parchment came from unborn animals, and was very expensive. It was not uncommon for lower grade parchment, which was more cost-effective, to contain holes and un-writable portions.

Because dye and parchment was so expensive (not to mention gold and silver illuminations), mistakes were often left in the finished product. Even some of the most splendid illuminated manuscripts leave in typographical errors. In the world-famous Book of Kells, kept at Trinity College in Dublin, one can find the occasional repeated paragraph and omitted sentence.

While many scribes had anxieties about working with such precious materials, others directed their complaints to the content of the work itself:

“Whoever translated these Gospels did a very poor job!”

“That’s a hard page and a weary work to read it.”

One Carthusian Monk from Herne thought he could do better than what he was given, and wrote next to his creation:

“This is how I would have translated it.”

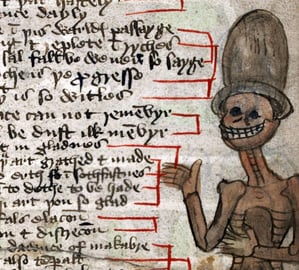

Curses

Because copying a manuscript was such serious work, scribes took it upon themselves to ensure that their efforts would end up in the right hands, and stay there. This is where the manuscript curse comes in:

Because copying a manuscript was such serious work, scribes took it upon themselves to ensure that their efforts would end up in the right hands, and stay there. This is where the manuscript curse comes in: “Whoever takes this book or steals it or in some evil way removes it from the Church of St Caecilia, may he be damned and cursed forever, unless he returns it or atones for his act.”

“If anyone should steal this, let him know that on the Day of Judgement the most sainted martyr himself will be the accuser against him before the face of our Lord Jesus Christ.”

Through curses, illustrations, complaints, and scrawlings, these medieval scribes have attained their own immortality.