Where does one even begin to talk about the British Library? As a strong contender for the largest library in the world, and as one of the most publicly engaged, the British Library simply cannot be contained in a short article. Its treasured manuscripts only scratch the surface, but it’s a surface worth scratching nonetheless.

Unlike some other long-storied collections, the institution of the BL is very young. Up until 1973, it was part of the British Museum and mostly housed in the (famously beautiful) round reading room. The British government then approved the creation of a separate library entity, which would combine the library department of the museum with the National Central Library, and the National Lending Library for Science and Technology. Several other collections were added to the proposed library, including the British Institute of Recorded Sound. For several years, the newly-created Library’s collections were scattered across London in disparate locations, but were finally collated in 1997 with the construction of a dedicated space next to St. Pancras Station.

Unlike some other long-storied collections, the institution of the BL is very young. Up until 1973, it was part of the British Museum and mostly housed in the (famously beautiful) round reading room. The British government then approved the creation of a separate library entity, which would combine the library department of the museum with the National Central Library, and the National Lending Library for Science and Technology. Several other collections were added to the proposed library, including the British Institute of Recorded Sound. For several years, the newly-created Library’s collections were scattered across London in disparate locations, but were finally collated in 1997 with the construction of a dedicated space next to St. Pancras Station.

Presently, the BL holds over 170 million items including almost 14 million books, 6 million sound recordings, 4 million cartographic items, and 350,000 manuscripts. Approximately 3 million new items are added every year, thanks to its status as a legal deposit library.

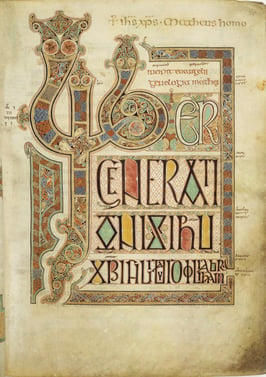

Every manuscript library needs an inaugural collection, and the BL had at least three of significance. Sir Robert Bruce Cotton had been a private collector in 16th and 17th century England who recognized the value of saving religious manuscripts after the Dissolution of the Monasteries. The Cotton library is most famous for the Lindisfarne Gospels (an illuminated manuscript circa 700), the oldest known copy of the epic poem Beowulf, and an original copy of the Magna Carta. The Harley collection (formed by Robert and Edward Harley) contains many illuminated manuscripts from the European Medieval and Renaissance periods, and the Sloane collection (bequeathed by royal physician and fascinating figure Hans Sloane) is comprised of many medical and scientific texts.

Every manuscript library needs an inaugural collection, and the BL had at least three of significance. Sir Robert Bruce Cotton had been a private collector in 16th and 17th century England who recognized the value of saving religious manuscripts after the Dissolution of the Monasteries. The Cotton library is most famous for the Lindisfarne Gospels (an illuminated manuscript circa 700), the oldest known copy of the epic poem Beowulf, and an original copy of the Magna Carta. The Harley collection (formed by Robert and Edward Harley) contains many illuminated manuscripts from the European Medieval and Renaissance periods, and the Sloane collection (bequeathed by royal physician and fascinating figure Hans Sloane) is comprised of many medical and scientific texts.

Needless to say, the BL has grown well beyond its seed libraries. Those priceless manuscripts now share display space with two Gutenberg Bibles, one of Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks, the Diamond Sutra (the world’s earliest dated printed book), Anne Boleyn’s copy of Tyndale’s English translation of the New Testament, and the original manuscript of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures Under Ground (aka Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland). And that’s not even counting the King’s Library, a royal legacy kept in a glass enclosure similar to the Beinecke at Yale. The library also collects more recent treasures like source material from The Beatles and original recordings of famous speeches from the likes of Nelson Mandela and Winston Churchill.

To boil the BL down to only its most famous items does the collection a disservice. For those who visit, there are permanent and temporary exhibits showing off the good stuff, but in addition to its “tourist destination” status, the BL is very much a working library. Anyone with proof of a permanent residence can apply for a reader’s pass and request to see items within the building for personal, work, or academic reasons. Countless scholars and artists have created great works with the help of the library. The BL is also on the forefront of digitization – browsing its online digital collections can occupy many, many wonderful hours.

In the world of libraries and special collections, the British Library is a monolith of knowledge and history: daunting, perhaps, but at the same time, an endless expanse that simply cries out for exploration.